On the Physics and Multiplicity of Time

by Aesc

I have had a terrible time with writing the things I'm supposed to be writing, and to help me the brilliant dogeared suggested that I do something maybe a little bit weird and a little bit different to see if I can't get myself back on track. Because I'm not a very adventurous person, I thought I would revisit the manuscripts from cesperanza's Written by the Victors; although I haven't thought much about them for a while, I remember how much fun they were to put together, and they're fannish but not quite fic, and kind of amusing to do in that they let me laugh at myself a bit. And even if it doesn't work and my mind still locks up when confronted with stuff that must be written, at least I had fun. Right? Right?

[Note: for stuff on the language, see here and here.]

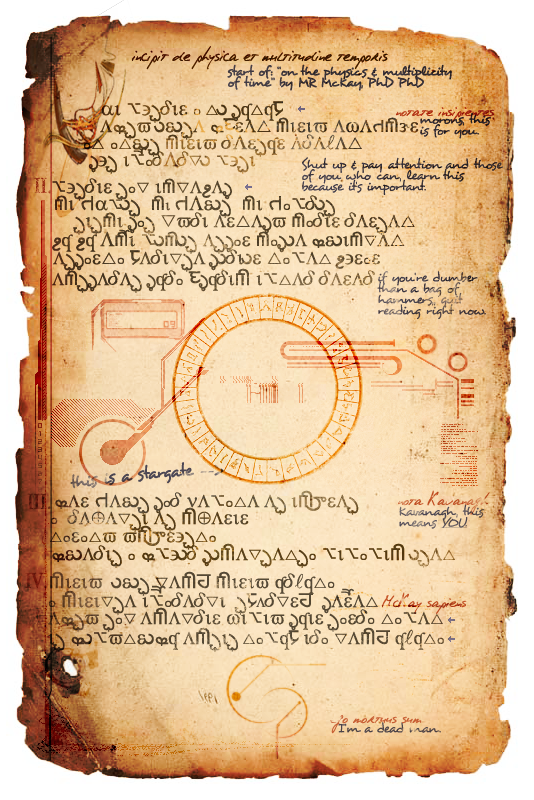

Seador, Liant Universat MS A197, f. 8v

TEXT

| Hnaui leisnir et to caitaith, apsu orosa paerat miriu afagmeir et etros miriu narsair anadhat ceis illenando, leisi. Leisnir sed imdavac mi gaulos, mi garos, mi gelnos sismi ces duni artacu menir narsat vai vai ammi lomos ascer mecoa proimdat ascerte thanidsa conior telat veirer, amskanas: caine! Aecainim iltan naran. Par garos, cen ngaleta as imbras e nahadsi as mharir, teretu umbreiste, proanis e pleion comadsatse tilelim osat. Miriu oros damoi, miriu aindhaite e miridsa illenandi skandroi carrat. Apsu sed Amadnir filiu Caiir serne telat is polutropai amsis telaith ine damios aindhaiste. |

Listen, student, and those who are capable (because this lesson reveals many secrets and unlocks many treasures for those who have discernment), learn. But, student, if thou wilt come like unto an ass, a fool, an idiot, like unto one whose mind hath the dimness of night even as a nail which hath rust thereon, and in whom is the stupidity of a gathering of bricks, I tell thee: Turn back! Turn thy face from me. Because a fool is a weight upon the heart and an anxiety in the belly and a trial to the nerves, and wheresoever he turneth his hand is disaster. For many are the worlds and many are the times, and their multitude surpasseth human understanding. But great is the knowledge of the creator McKay, and he has as many ways as there are worlds and times. |

COMMENTARY

While it is not the purpose of this commentary to explicate the doctrines of Rodney McKay (this has already been done in the exemplary work of Queroen 1100; see Samnad Archivist F9q-3S), no discussion of De physica et multitudine temporis (On the Physics and Multiplicity of Time) can be complete without acknowledgment, at least, of the impact the text has had on latter-day science and philosophy. Of its companion texts in the Liant Codex, the De physica is the most widely-attested work, with five hard copies known to exist and, by now, innumerable electronic versions. It is likely that the De physica's existence in text is wholly responsible for its preservation; the early loss of the memory-ship Theseus, which had a significant portion of its storage devoted to the sciences, meant that the first several generations of post-Ori Terrans had, almost virtually, lost everything except for what hard copies of their texts survived. Even a millennium after the Return, we remain confronted with a heritage so broken, so scattered, even the most brilliant scientific minds among us stumble blindly.

The De physica is, fortunately, one of the few bright lights we have to guide us back to what once was; it is the text central to the doctrine of the Quaerentes in their attempts to regain the scientific utopia of the Lantean golden age, and likewise serves as the foundation text for university coursework in physics and metatemporal philosophy. Even without taking the text's contents into consideration, its preservation in the Liant Codex (on ff.8v-15r) and the intimate association of that codex with the familia of Rodney McKay and John Sheppard alone would secure it a place as one of the most important works in our intellectual and cultural heritage. While today we would recoil in horror at the thought of defacing a manuscript, the leaves containing the De physica show signs of use, lightly glossed in a Skani proto-Lantean variant as well as a colloquial form of Anglo-Lantean.

In terms of content, the De physica represents a sustained attempt by a fairly competent poet to render Amadnir McKay's extensive knowledge of wormhole and temporal physics in Skani verse, poetry being the traditional medium of Skani education. The opening four verses, composed in free-verse (but with occasional markers of more traditional poetic forms, such as envelope pattern and alliteration), establish both the necessity of knowledge and the unfortunate fact that many who attempt to read the De physica will lack the mental faculties to understand it. The derisive tone of these lines, and the way in which the glosses echo it very closely, suggest that the writers of the glosses were sympathetic with McKay's need to keep the De physica away from those who would misuse it. The gloss in the top margin, M.R. McKay PhD PhD identifies McKay explicitly, while the PhD PhD has been taken by Ganides (1081) as a deliberate deformation of the very early Skani pharad pharadir, "god of gods," and interpreted by Tolor Nehagani (1092) as evidence that the De physica, even from its beginning, was considered a sacred text.

Of course, historical arguments suggest that Ganides (linguistic brilliance aside) and Nehagani that the opening four verses may simply constitute very emphatic evidence of McKay's impatience with those whose minds were less than agile. From what is known of Amadnir McKay, who is described by Ronon Dex as "a guy who talked a lot--a whole lot--but I've seen him shut people up just by looking at them" (Works and Days 2.599; see Nakaia Archivist L2m-1J), it is possible he dictated the raw material for the De physica, which was then reworked by a Skani poet. This is the view taken by biographer Romara Iscorides in The Creator; her close study of contemporary texts dealing with McKay has brought to light a particularly fascinating exchange between McKay and soerni Sheppard regarding a matter which, while mysterious to us, was obviously of significant importance to them:

"Oh my god, Sheppard, seriously, could you be any more... any more..." Sciens McKay stops talking, I think because he is no longer capable of doing so.

"Any more what?"

"Oh, I don't know. Obnoxiously petty? Twelve years old? Five years old? Honestly, erasing my high score, I ask you. Do people outside of myself, Teyla, and Ronon know you behave like this?"

And then Lord Sheppard says, "I don't think so."

"You're very convincing at playing dumb. Too convincing." Sciens McKay pauses; I cannot see him, but I imagine he has his eyes closed (as he often does in the labs, when attempting not to shout at the new scientists). "I demand a rematch. The Augusta Masters, eight o'clock. Don't be late."

Although the source is an admittedly sensationalist memoir, the anonymous In the Halls of the Ancients (Yahara Archivist L4i-3G), the more reliable autobiography of Praxane of Anos, a scientist who moved to Atlantis shortly following the Secession, refers frequently to McKay's legendary loquacity and capacity to frighten his subordinates: "I had thought myself knowledgeable," she writes ruefully, "but I spent that night crying in my room with Cleis [her wife], who provided little comfort" (Idemon Archivist H6e-8N). Later writers seemed compelled to memorialize McKay's impatience in addition to his unparalleled brilliance; the anonymous composer of the Return-era Hymnus ad Filium Caii conditorem refers to McKay in the same stanza as "the light above all lights" and the "thunder-voiced one, whose eye burns as blue fire and in whose mouth is lightning" (Thales 1112).

Iscorides' analysis of the Liant De physica leads her to conclude that the Anglo-Lantean glosses are the work, not of a student of McKay's (for which, see Brahan 1099, Yahara Archivist 1110), but of McKay himself, as a way of emphasizing the extent to which he considered the De physica's knowledge to be sacrosanct. The Quaerentes share this attitude, and look on the wide dissemination of the work as sacrilege; initiates into the order are forbidden to study the De physica until they have successfully completed the ten years of their novitiate and the pilgrimage to Old Atlantis, where it is said that Amadnir McKay will address those he deems worthy of full admission to the order. Iscorides' pro-Quarentes leanings are perhaps most apparent here, and it is well to take her conclusions regarding the glosses with some caution.

A useful, although perhaps radical, corrective to Iscorides is the work of the late philosopher and critic Raheb Pythan. The Capture of Time (1118), his most famous work on the critique of traditional metatemporal philosophies, is in part a critique of Quarentes-based approaches to physics and related fields and seeks to move science beyond what he saw as the modern-day obsession with, essentially, "resurrecting" Amadnir McKay:

Recapitulating McKayian paradigms of spatiotemporal theories is well and good," reads his most contentious passage, "but have we not been returning to him for centuries, and have we not failed to find those shrines where, as some people would have it, we will be restored to all the knowledge that has been lost? I argue the only way for the sciences to survive--even, at the most fundamental level, to live--is for us to break free of McKay-derived theories and re-vision the universe for ourselves. (181)

To be sure, Pythan has his supporters, and in the two years since the publication of The Capture of Time, some scholars have advanced theories that may prove to be bridges between lost forms of knowledge and original discoveries. Still, these discoveries are likely to be based on new interpretations of the De physica and other texts in the McKay corpus, which forces Pythan to admit that, in the final assessment, "even across dividing time, his hand steers us yet."

Ronel Macara

Year 1120 of the Return

Liant Universat

Lux fiat pastore scienteque, et lux eorum vobis effulgeat.

The End