Through Cities And Churches

by Speranza

Author's Note:

Thanks to lim for mucho cheerleading and handholding and nitpicking and brainstorming all the way through! I think I'm done fixing Civil War now - onward, upward, and beyond!

Also, if you liked, please consider reblogging on tumblr!

Prologue.

It seemed only right to be standing over the empty grave of an undead man. The file Natasha had given him was stained, well-thumbed, a bit ragged at the edges. Bucky's face was gaunt and frozen under glass; a death mask. Clipped to that ghastly photograph was the Bucky he recognized: warm smile, jaunty tilt to the hat. Steve snapped the pages shut, his fingers pressed white against the manila. Cyrillic writing. Case No. 17, Volume 2, March 23, 1945—Christ.

"You're going after him, aren't you?" Sam asked, and Steve gritted his teeth to stop the words from spilling out: yes, of course he was, and if he'd gone after Bucky all those years ago, after Bucky had fallen, he could maybe have saved Bucky all these years of fucking torment—

"You don't have to come with me," Steve said finally.

"I know," Sam said, and then he sighed and said, "When do we start?"

"Soon," Steve replied absently. He slid the folder into his jacket and zipped it, and later, he realized this was the moment he'd stopped telling polite untruths ("That's fine," "I don't mind," "I'd be happy to,") and started telling outright lies, because he'd already started searching for Bucky and he would never stop, no matter what.

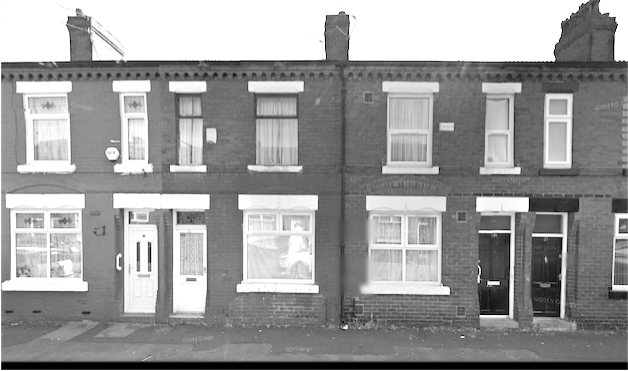

It was hard to be in Brooklyn now, because so much of his Brooklyn was gone. The old streets had been overshadowed by the thundering BQE, which was new to him but had steel rusty and rotting underneath. The wood-framed tenement where he and his ma lived was gone, replaced by some dingy apartment buildings, and where his and Bucky's flat had been there was nothing but a brick wall rising up and up to the roaring traffic overhead.

The Barnes house was still there, though the block was full of rich people now. Five years ago, there would have been kids, playing stickball or jacks, and he could have asked them what was going on, because the kids on the block would have known everything. But there were no kids playing, and Steve felt self-conscious loitering, so he turned the corner and made his way back toward Atlantic. He wasn't going to find Bucky here: not anymore.

But he couldn't shake the feeling that Buck was nearby: he felt it in his bones that Bucky would come back to Brooklyn. Steve had wandered this same downtown loop over and over when he came out of the ice, trying to believe his eyes: that it had been seventy years, that everyone was dead. Oh, sure, some things were the same—Goldie's and Tom's, and the Cyclone was there—but they were ruined by the ugly white lights they used now, so hard on the eyes. High up on the brick sides of buildings he could sometimes see the remnants of painted signs: GOLD MEDAL FLOUR or CHESTERFIELD CIGARETTES or ROOMS $1.00 WITH BATH $1.50. He became an expert at spotting these signs, which were like meeting old friends: signs for the IRT, for Omega Oil and Singer Sewing Machines. He'd even found a sign he'd lettered himself, for the Chandler Piano Company, though only the "CH" was visible and the store was now something called Edible Arrangements, which sold bouquets made of fruit.

Steve wandered on, looking down at the sidewalk or up at the buildings' cornices, and he didn't realize where his feet had brought him until he found himself outside a café of white wood tables ringed with flowerboxes. It wasn't immediately familiar to him, and he had to look up at the cross street—Henry—before coming to himself with a jolt; now he knew where he was. But it all looked so different. Steve covered his shock by stepping forward and staring down at the menu, which was in a glass case on a pole. Nicoise Salad—$26.00, Steak Frites—$38.00—and he still couldn't get used to those numbers. A blonde in all black smiled and asked him if he wanted to sit outside, but no; no, he didn't: what he wanted was a seat inside at the bar, if that was all right. Yes, that was just fine.

The place was empty at this hour—just a few late lunchers sat outside in the sunshine—but in Steve's memories it was crammed: four deep at the bar, a live band squashed in the corner, couples with their arms and legs flying. People expected him to think things were more crowded now, but back where he was from the streets were teeming. There had been streetcars and pushcarts and horses and sometimes a chicken running loose. Now everyone did their living indoors, but back home with no TVs or computers, living five to a room, you had to find someplace else to be.

The bar was in the same place, but it wasn't the same bar: this one had a long slab of white marble on top. The walls had been painted white and there were enormous pots with flowering trees growing out of them. Steve nodded at the bartender and ordered an onion tart and a pint of whatever was good on tap before sliding his hands into his pockets and casually strolling around the empty tables. He pretended to look at the (terrible) fake impressionist paintings before turning to his actual area of interest: the two built-in bookcases along the back wall. They'd been painted white, too, and the shelves were covered with knick-knacks rather than books: little punched-tin candle-holders and an antique coffee grinder and a chalk board which read Bon Appetit! Steve pretended to look at the book titles; actually he was studying the joins where the bookshelf fitted into the wall. They were thick with layered paint.

"Onion tart?" the bartender called, and Steve said, "Yeah, that's me," and slid onto the stool. The guy was about his age but skinny, with shrunken-on jeans and a beard. He rolled some utensils in front of Steve with a vague smile.

Steve asked casually, "How long have you guys been here?"

The bartender considered. "About six months, I guess. Why, are you looking for a job?"

Steve grinned; if there was a job on offer, he just might take it. "You think I look like a waiter?"

The bartender lifted his eyebrows at him. "Like an actor," and Steve burst out laughing. The bartender put his elbows on the bar and said, friendly: "Hey, no judgments: just you're clearly working your look, man."

Steve reached for his pint. "I've done some time on the boards," he admitted.

"Oh, a stage actor—you guys are crazy. Dude, TV is so much easier. Let go of that theater shit. Not that I need the competition, but." He shook his head ruefully. "They're casting extras out of Astoria next week if you need something to tide you over. Pay's not bad if you've got your card."

Astoria? The old Army Studios, Steve realized. "I did a movie there, once. Three actually."

The bartender suddenly pointed at him. "Hey, wait, I know you," he said. "You did that toothpaste commercial a couple of years ago—Crest. Minty white freshness, right? With the dog?"

"Uh-huh," Steve replied earnestly. "Yeah. That was me."

The onion tart was good enough that he ordered a second one and another pint of beer before settling up his tab with the place: La Mirabelle, it said on the ticket. Well, that was a change; it had been Spodieodie's before, though no sign ever said so. Steve left the bartender a good tip and wandered back out onto the street. People were coming home from work, pushing out of glass office doors and streaming up from the subway. He walked around the block and down the street behind it, wondering if you could still get into the alley behind Spodie's by cutting in between the buildings on this side. Turned out you could, if you could get past the chain-linked gate that now blocked the alley. Steve took the old lock in his hand. It had already been broken and hung there, uselessly.

Steve stayed close to the wall as he moved toward the back of Spodie's on the off-chance that someone was watching. There were crates and boxes stacked behind the restaurant, and the door to the kitchen had been propped open to let out the heat; some things never changed. Steve looked up at the second floor, where there were one, two, three windows—but he knew for a fact that if you were to go up to the second-floor, there were only two windows on the back wall. That third window was a ghost window, and he could only hope that a ghost lived there now.

He hesitated for only a moment. It was still a straight shot: a quick hop to the top of the low wall, and then he could just ease open the window and slide over the sill. He and Bucky had done it millions of times, and they'd always left the window unlocked and opened a finger's width. He looked around quick, then hopped up and slid his fingers under the splintered wooden sash. It was open. His heart was pounding. He eased the window open and ducked under. And then he stopped, still clutching the window frame—because Bucky was there, hunched in a corner with his back to the wall and a gun in his lap. He was staring at Steve with a kind of blank incomprehension. He looked ready to spring, and Steve immediately raised his hands: empty, no weapons, no shield, no nothing, Buck; just me.

"I hoped you'd be here," Steve said finally. Bucky didn't reply or even move.

"I didn't know if you'd remember," Steve went on finally. "I barely remembered myself."

Bucky looked hard-faced and gaunt, but he was surprisingly clean, considering the flophouse conditions. The little room was just like Steve remembered it: the same dusty plaster walls and picture frame moldings, the same scarred wood counter and slop sink. Steve could only see the one gun, which was reassuring; there were no signs of the Winter Soldier's vast arsenal. Even more heartening were the signs of normal humanity around the place: a white paper carton with chopsticks sticking out; a backpack and denim jacket; a phone. Best of all was the thick notebook on the floor near the unlit lantern; Bucky'd always carried a notebook with him, even during the war.

Bucky's notebook...but this wasn't Bucky somehow; not exactly; not quite. The Winter Soldier's murderous intensity was gone, but the guy sitting there was still more Winter Soldier than Bucky Barnes, staring forcefully at him like he was trying to remember Steve, like he knew he should remember Steve, but somehow couldn't.

Steve screwed up his courage. "Do you know who I...?" Something pained crossed Bucky's face and he gave a little shake of his head, almost a twitch, like a dog; I don't.

"Okay," Steve said immediately. "That's okay." It didn't feel at all okay. "You knew to come here, though." Steve lowered his hands a little, and when Bucky didn't react, he lowered them all the way. "We used to come here all the time, you and me, before we got the place on Furman—" and Steve stopped because that had got a reaction: the first real one since he'd walked in.

Bucky's voice was a scrape, and so beautiful. "It's not there anymore."

Steve felt a strange relief. "No, that's right," he said, trying to keep his head: Bucky'd gone home, or he'd tried to. "It's not there anymore; it's gone. Your old house is still there, though—" and that got a reaction, too; a bad one: Bucky suddenly looked like a trapped animal, eyes panicked and dark. Steve fumbled to move the conversation away from the Barnes house, the Barnes family. "This building," Steve hurried on, "was a bar, remember?"

"I—yes." Bucky's eyes were black, darting, but he seemed to be bringing himself under control.

"It was Jimmy Mac's place, everyone called him Uncle Jimmy," Steve said.

Bucky licked his lips, looked up at him, nodded. "Spodieodie's."

"That's right." Steve drifted closer and went to his knees on the floor, ignoring the gun. "We worked here when we were kids—two years, hauling kegs and big jugs of red wine. All the bottles and mash for the fruit juices and mixers. Washing glasses—you remember how many glasses I washed?" Steve couldn't stop himself from smiling. "I must have washed thousands of glasses."

"Thousands," Bucky repeated vaguely, and then he was reaching for his notebook and writing something down, scribbling in what looked like a mix of English and other languages besides.

"And that's how we knew about the door, the secret door downstairs. Behind the bookcase." Bucky lifted his head from the notebook; his eyes were far away but he was nodding vaguely. "We loved the secret door," Steve added, his voice instinctively dropping, "because it was like something out of Dickie Malone and the Rats of Sunderville," and Bucky's whole face changed then, lit up like Times Square. He remembered! God bless Dickie Malone!

"For the...speakeasy," Bucky said, finding the word. "They kept the booze up here."

"Right," Steve said. "And then later they closed it again. When the booze became legal."

"In '33," Bucky said.

"Right." Steve's heart was banging painfully in his chest. "Jimmy sealed it up, but he said it was always good to have a place like this that nobody knew about, like something in your pocket."

"But we knew," Bucky said, and looked at him.

"Yeah." Steve could hardly breathe. "We knew."

"So we came in through the window." Bucky looked at the window, and Steve actually held his breath, wondering how far he would get. "Because we knew there was a room up here."

"Yeah," Steve managed.

"When it rained," Bucky said.

"Yeah." They'd been sixteen, seventeen; they'd smuggled up rotgut and dirty pictures, Tijuana bibles; they'd played cards, smoked; listened to games on the wireless. Steve had brought up his sketchpad. They'd hid from anyone looking for them, nursed their bruises after fights. They'd...

Bucky's brow furrowed. "We had a secret room," and then Bucky looked at him and Steve's heart leapt, because Bucky'd gotten there after all. "Because we had a secret."

Steve held the tears back. "We still have it, Buck," he said.

Bucky didn't do anything for an endless moment, and then he was reaching out to grip Steve's shoulder, the first non-violent touch between them since....no, wait. Steve had a sudden, sure memory of the Winter Soldier reaching for him underwater. Bucky had dived into the Potomac, had pulled him up and dragged him to shore. Now the metal hand was tight on his shoulder and Bucky was leaning across, between them—to kiss him, Steve realized. He felt surprised, happy, only a little shocked. The kiss was just a press of lips and gone, curious and exploratory: nothing like kissing Bucky had been. It was awkward in a way they'd never been with each other...or was that right?

The Winter Soldier stared out of Bucky's face. No, that wasn't right. They had been this awkward with each other once, or once upon a time, anyway. Steve thought back past his memories to older ones, to those first few nervous kisses—right here, back when they were kids, ages and ages ago. They'd been scared half to death, he remembered. Of themselves, of each other. Of their bodies: of what they could do, of what they wanted to do. Bucky was looking at him now with an intensity that Steve realized was at least partly fear: he still didn't remember most of everything. Bucky didn't remember him or this or any of it, or maybe he only half-remembered it, like yesterday's dream.

He realized that Bucky was looking to him for a reaction—and he was just sitting there like a dope. "We did this," Bucky said uncertainly, asking for confirmation. "You and me."

"Yeah, Bucky; yeah," Steve said with sudden fervor. "This and more," and then he was leaning to kiss Bucky back—gentler than he wanted to, because if Bucky didn't remember how it had been with them, it would maybe be too much, all at once. So he kissed Bucky more carefully then he would have, because Bucky had all the Winter Soldier's stillness and self-control and he was letting it happen but not participating—until suddenly he was.

It was subtle at first, so subtle that Steve barely noticed the movement of Bucky's lips against his, and then he felt Bucky's fingers tangling in the fabric of his shirt, and then everything shifted. The kiss became real, Bucky's mouth moving with greater certainty, like he was remembering how to do this—and he probably was remembering, because the Winter Soldier had been treated like a goddamned piece of machinery. They hadn't let him be a person. They hadn't let him have a body.

This time when they pulled back, Bucky was breathing a little fast—which was nothing like the Winter Soldier, who had seemed never to breathe at all. Steve grinned stupidly at him, then grabbed his face and kissed him once, twice: two real intense smackers—he couldn't help it. Bucky stared at him, but Steve thought he maybe detected the faintest hint of a smile, somewhere deep underneath.

"I read about you in a museum," Bucky said finally. "And me," he added offhandedly, and Christ, Steve thought that only thing worse than Bucky having to go to the Smithsonian to learn about one Steven Grant Rogers was the idea of Bucky Barnes having to go there to learn about himself. And then Bucky surprised him by saying, wryly, "They didn't say anything about this," and Steve burst out laughing at the idea.

"Well, they wouldn't, would they," he admitted.

"'Friends since childhood,' they said." Bucky looked at him, almost accusingly.

"Nothing about banging since the end of Prohibition?" Steve inquired earnestly.

"Not a thing. All heroism and patriotism."

"Did you look in the back?" Steve asked. "There was a picture of me in a dress with a little white card saying ..."

He stopped, because Bucky was wearing that look of anxious concentration again, like he was struggling to plug the holes in his memory. "Friends since childhood," Bucky repeated.

"Yes," Steve swore, and Bucky stared hard at him with eyes that were full of the Winter Soldier's suspicion. Steve's heart was hammering again: Bucky had to remember him: had to.

Then Bucky said, softly, "You were smaller," and Steve let out a painful breath and shot back, "Well, so were you," and Bucky considered this for a moment before conceding, quietly, "I guess."

Truthfully Bucky hadn't been much smaller before the serum; even before the war he'd been big enough that Steve had been able to straddle his legs and sit in his lap. He used to sit on Bucky's thighs with his pants unbuttoned and Bucky hard beneath him, kissing and teasing till he brought Bucky off. They'd done that in this very room before they'd had their own place and their own bed. It had felt so crazy, so dangerous. Steve wanted to do it again right now.

Bucky's pupils widened like he could feel Steve's desire pulling on him. "What do you think?" Steve murmured, and took off his jacket; he could go slow, he could be patient, because if Bucky didn't remember it, it was like it hadn't happened. He unbuttoned his shirt. "You want to try? Can you trust me this far?"

Bucky flicked his eyes down and up, down and up Steve's body, his expression torn between longing and suspicion, but he took the gun out of his lap and put it aside before sliding his arm around Steve's neck. Already it was easier to kiss; already it was more like before. Bucky cupped his head like he used to, and their mouths moved against each other intensely, like they were communicating again, and—Steve nearly broke it all to pieces but recovered fast, shaken—stupidly—by the scrape of metal plating against his hand, the edges of the thick scars.

He covered for his shock by sucking on Bucky's lower lip and pushing him down into the nest of blankets, rougher than he'd meant to. He dragged his hand down Bucky's chest. His shirt was hanging out of his pants at the front and Steve shimmied his hand past the waistband, slid his buzzing fingertips over the warm cotton. He gripped Bucky's cock—hard, full, hot—through the fabric. Bucky let out a wet sound of surprise, like he'd forgotten what this feeling even was—Christ, they'd probably never even let him masturbate; and hell, when would he have? Steve tightened his grip—cramped, fettered by Bucky's clothes. He couldn't stand it. He had to get closer. He yanked open the snaps and buttons and pushed it all aside. His mouth watered and he licked his palm and grasped Bucky's cock. Bucky went still, so silent and focused that Steve could hardly tell he was breathing. But Steve was breathing hard enough for both of them, loud in the quiet room. He lowered himself on top of Bucky's body, buried his face against Bucky's warm, stubbled cheek, and began to fondle and stroke him, gripping his cock, gently cupping his balls.

He went slow, sensing that Bucky needed him to go slow: that Bucky's body was only slowly remembering what pleasure was. Steve understood—his own body had been dead to him after the ice. With his memories of Peggy and Bucky tainted by loss and pain, even fantasy had been impossible—and real people, well: the less said about that, the better. You couldn't will attraction, and nothing in this modern world compared with Peggy's body hugged by a red knit dress, or the slow, sexy slide of Bucky's tongue over his lips, searching after a stray fleck of tobacco. Crude talk and cruder images were everywhere here in the future, but sex appeal was gone—well, for him, anyway.

Bucky was leaking into his hand, and suddenly, the breath bursting out of him, Bucky shuddered and said, "Oh. God. Oh—" and twisted his head so they could kiss, or at least pant into each other's mouths. Bucky clumsily grasped for Steve's shoulder, his back, like he was trying to remember what to do, how to move, hips jerking awkwardly—and all at once it was like they were sixteen again: sixteen and here in this room and they were going to figure it out, they were going to figure this whole sex thing out together. Steve hooked his leg over Bucky's so he could rub against Bucky's hip, get a little friction for himself. He felt sixteen, too—his body had come roaring back to life, cock and balls pounding, aching to be touched. Even his nipples were—and Bucky convulsed against him, his cock pulsing wetness across Steve's arm, between their bodies. Steve moaned softly and stroked him through it. He helplessly grabbed Bucky's hand and dragged it to his chest, speaking with his fingers: touch me, just touch me. He grasped himself just as Bucky cautiously stroked a thumb across his nipple—and then it was like Bucky remembered this, too, and began pinching and rolling his nipples, sucking hard kisses against Steve's jaw and neck.

A warm, pulsating pleasure washed over him. He'd forgotten these feelings. Bucky's tongue slid wetly into his ear and Steve jerked and came in a rush, his whole body surging, convulsing. Christ, that was good: he'd literally forgotten how good sex could be. The rush of fighting, his only real pleasure now, was nothing to it. Tears stung his eyes and he held them back. He was still shaking through it when Bucky surprised him with a kiss: intense and heartfelt, and totally different than that first mechanical press of lips. "Steve," and then stupidly, the tears came, because having Bucky say his name brought all the loneliness back full-force: nobody'd said his name for ages.

"Steve," Bucky said again, hesitantly reaching for him with his metal arm, and it wasn't like being sixteen anymore; it was like Azanno, and him and Bucky clinging in the dark.

He heard himself saying, "I'll take the watch. Let me take the watch," and when Bucky's face twisted with hunger, he knew he had been right. "How long since you slept?" but the look of half-desperate incomprehension on Bucky's face was all the answer he needed. "I'll take the watch," Steve repeated. "Trust me, I'll take care of you," and still Bucky's eyes stayed open but Steve could almost see him falling asleep somewhere beneath, and he had passed out long before his eyes finally closed.

Or had he? Bucky's eyes opened again, or maybe it was the Winter Soldier who couldn't let himself rest. "I can't come in," he said in a voice that was both frightened and strangely blank. "I can't come in yet."

"Okay," Steve said, responding to the distressed tone of Bucky's voice.

"I'm not ready to come in. I'm too—I can't. Not yet."

"Okay, Buck," Steve repeated. "If you're not ready to come in, then don't. You don't have to. I won't make you," and that seemed to relieve Bucky's mind, because his eyes finally drifted closed and stayed closed.

Bucky didn't wake up panicked, or pressing a knife to Steve's throat. Instead he opened one blue-gray eye and squinted up warily. "Do you know me?" Steve asked him, braced for disappointment.

"You're Steve. I read about you in a museum, but I never got to the part about us being queers."

Steve felt almost lightheaded. "Oh yeah? What about my long career in burlesque?"

"That neither," Bucky said.

"Well then, you missed out," Steve said. "That was the best part. There was a picture of me and Josephine Baker, doing the banana dance," and then, without missing a beat: "Look, if you don't want to come in, maybe I could—"

"No," Bucky said, shaking his head.

"—stay with you," Steve went on, like Bucky hadn't said anything. "Or go with you, if you don't want to stay here. I'll go anywhere you want."

"No," Bucky said again, and this time Steve had to reckon with his answer.

"I want to stay with you," Steve said. "Why not?"

"Because," Bucky said, in his talking-to-an-idiot-child voice, which at least was familiar, "I need to be a cockroach, a rat in a hole, and you're the bright and shining light of justice. That part was in the museum, real clear."

"That's him, not me," Steve protested, aggrieved. "That's Captain America. That's—"

Bucky was having none of it. "Steve, you don't know how to keep your head down and you never did." Steve exhaled irritably, but he couldn't really argue. "Besides—" Bucky's mouth tightened. "The only people looking for me are people who hate me and want me dead," and before Steve could protest, Bucky went on, unexpectedly, "It's a huge advantage. Because they don't want to find me; not really. They're just afraid of me, of what I'll do. They'd be happy if I just went away. But if you disappear, the people who'll come looking for you—they love you, and that's much worse. Because they'll find you. They're not going to stop until they find you."

"It's not only people who hate you who are looking for you," Steve managed.

"Yeah and you found me, didn't you," Bucky pointed out. "That's how I know that you—you know." He flushed.

"I do; I love you," Steve said, throat tight.

Bucky looked like he couldn't believe Steve really said it out loud. "I—believe it," he scraped out, and kissed Steve in the old way, ripe and urgent. Steve closed his eyes and let himself revel in it. Then Bucky moved his mouth to Steve's ear and whispered, "But if you do, you have to let me go. Draw them away from me, buy me some time," and Christ, he had to fight the urge to argue, to beg and plead: No, don't go—I haven't got anything else; nothing; not a single goddamned thing—but he couldn't put all that on Bucky, not when he had only just gotten free.

"If I do, are you going to be safe from Hydra?" Steve asked.

Bucky nodded, so Steve went on to the other question, the terrible question: "Buck, are people going to be safe from you?" and he regretted the grimace of pain that crossed Bucky's face, but he had to ask; he had to know.

"Yes," Bucky said vehemently. "Yes, Steve. I swear to God."

"Then, okay," Steve said. "Okay. I guess we'll do it your way for a while."

"Where the hell have you been?" Sam asked, turning up on his doorstep in Dupont Circle. "I figured I'd see you running on the Hill one of these mornings, but you never showed."

"Sorry," Steve said, idly scratching his neck. "I went to follow up a lead and—"

Sam shot a narrow look at him. "I thought we agreed you weren't going to do that. I know you think you can trust him, but it doesn't hurt to bring backup. That guy's been through a lot and—"

"It didn't pan out," Steve interrupted, then forced a smile. "So." He jammed his hands in his pockets and shrugged. "I got another lead, though, if you want to come with. In Chicago," he said. It was the first place he could think of.

"I'm in," Sam said, and then, warming: "Chicago's a great town," and Steve nodded, relieved. He'd pay for the trip and buy Sam a steak dinner, and maybe that wouldn't quite make up for lying and dragging him around on a wild goose chase, but it all he could think of to do.

The letter, when it came, was marked "RETURNED FOR POSTAGE," and it was addressed in his own handwriting, though he couldn't remember sending it and knew he hadn't. Still, those were his initials, and the return address the way he always wrote it—SGR 1614 Hillyer Pl., DC 20009—because he liked to write letters, though people rarely answered in kind. People replied to Steve's letters either with telephone calls or short texts or e-mails, and businesses replied to his queries with form letters that never directly addressed the questions he'd asked.

But this was an actual letter as well as a damn good forgery of his writing, which made Steve smile even before he saw that the letter was addressed to Dickie Malone of Sunderville, New York. Steve carefully opened the envelope and took out a piece of paper. It said—

AOIIOREYFEAHOERHTSLCTLRTESHR8TEFTEYBOLOALTTCSD

—a string of carefully printed letters in his own handwriting. Steve looked down at it for a second and then he was laughing out loud and crossing to the desk, slapping the paper down and bending over it. He fumbled for a nub of pencil: he hadn't thought about this in years. When they were kids, he and Bucky had sent each other letters like this, without postage and with the delivery address and the return addressed switched. They'd thought they were so clever to think of it. And they'd both of them learned a bunch of ciphers and secret codes, taught to them by the heroes of their favorite wireless serials. Bucky'd always loved Lamont Cranston best, but he'd gone with Steve's suggestion: the tough-as-nails gang leader Dickie Malone.

He was surprised at how quick it came back—draw the boxes, fill in the letters. He and Bucky had invented a whole cipher table when they were kids. Then he started breaking the code, making substitutions, except it didn't seem to make sense, even broken. The letters went—

KCOLCOEERHTYADIRFEROMITLABTEERTSLEHTEBHTUOS181

—and Steve stared down at them for a minute before grinning: Bucky'd given it to him backwards. He copied out the letters in reverse, then separated them with slashed lines:

181 / SOUTH / BETHEL / STREET / BALTIMORE / FRIDAY / THREE / OCLOCK

Right. Steve sat down slowly in his leather desk chair, his stomach churning with excitement. Baltimore. Baltimore was damn close. Steve committed the address to memory—181 South Bethel Street—and then pulled open the center desk drawer and took out a matchbook. Then he lit the letter and its envelope on fire and watched them burn.

Baltimore was close enough that he could drive there, but at the last minute paranoia hit him and he left his motorcycle and went to Union Station instead. He bought a ticket to New York but got off in Baltimore and took the bus. The neighborhood had few trees, and trash littered the bleached and cracked sidewalks. Steve got off the bus at a deserted intersection of brick row houses. A small and battered "FOOD MART" sat caddy-corner at the intersection: the whole place felt more like Brooklyn than the upscale steel and glass buildings of Atlantic Avenue.

He set off down the street then turned the corner at an abandoned lot so overgrown with weeds that it was almost a meadow; this was South Bethel Street. He'd imagined checking the street numbers except there was almost nothing here; an empty schoolyard, a single decrepit apartment building...and at the end of the street, a church. Steve walked toward it with inexplicable certainty; this was the place. The years were dropping away: something about the road, the pointed gothic windows of the church, made it feel like the past. The sidewalk had been swept; the small garden behind the wrought iron fence had been weeded and cared for. Letters in a glass case proclaimed: ST AUGUSTINE PARISH. Mass Schedule: Weekdays 9 AM, Saturday 5PM, Sundays 9 AM, 12 PM (English) 10:30 AM (Spanish) 5 PM (Polish). Confession and Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament: Friday 3 PM, Saturday 4 PM. ALL ARE WELCOME. The huge wooden doors had been propped open. Steve stepped into the cool, empty vestibule. He dipped his fingers into holy water and crossed himself before opening the inside door and going into the church.

It was narrow and high-ceilinged, with a long aisle leading down to the altar: gothic revival. Steve's eyes went straight to the art. The statuary—two angels flanking the tabernacle, the Virgin Mary and the Infant Christ, St. Augustine holding his staff—had been painted in red and blue and pink; the Stations of the Cross had been sculpted in bas relief. Steve moved slowly down the far aisle and then slid into a pew and sat down: what activity there was seemed to be centered on the tiny side chapel where the monstrance had been set up for the adoration of the Eucharist. Steve stared down at his hands. He supposed he should go sit there with the few other people in the place, but it seemed wrong to pretend he was here for Christ when he was here for Bucky, so he stayed put.

The minutes slowed. He was more comfortable in church than in most places—less had changed here than in most places—and he supposed that Bucky must feel the same. Candles had been lit in front of the Virgin. There was the scent of incense in the air. It could be 1926 or 1936 or 2016—and Bucky slid into the pew and sat down beside him.

He looked worse; no, that wasn't quite true. He'd put on weight, and his skin had lost its sickly white cast, but misery had carved deep lines of unhappiness into his face. He seemed to have a faint tic; his right eye fluttered. "Hi," Bucky said, and then he must have read Steve's distress off his face, because he added: "I'm all right."

Steve wasn't sure what to say. "I've been worried," he said.

"I meant to be in touch sooner, but—" Bucky stopped. "I wasn't anywhere, so I had nowhere to ask you to. I've been living in shelters," and oh Christ, that saddened him, angered him—but Bucky raised a hand and said, talking over him, "which was good for me. Like the army: normal; lots of guys with B.O. and stinky feet. Plus I've been moving around a lot," and then he was hauling his backpack up onto the pew between them and rummaging inside it.

Bucky had more than one notebook now, and he frowned between them and then handed one to Steve and shoved the others back inside. Steve double-checked Bucky face for permission and then opened it and began to page through Bucky's scrawled jottings, diagrams, and maps, the occasional taped-in column of newsprint. This was Hydra, Steve realized: mostly people and places. Bucky'd drawn maps of bases, drawn squares around names in block caps: Santiago, Pyonyang, Kandalaksha. There were contacts, maybe handlers—Wm. Kruger. Hans Caldwell. S. Rowland. B. Hess—page after page; Steve recognized a few of them. Some of the names had checkmarks, or were slashed through or crossed out; others had cryptic notes written next to them in English or Russian ("The Hangman" or "Я не понимаю") or sometimes just frantic question marks or dashes (————?!!)

Bucky took the notebook back, turned to a particular page, then pushed it back into Steve's hands and tapped it with a finger. "Most of these guys got culled in Romanoff's info-dump," Bucky said quietly, "I cross-checked. But there are some who weren't. I—handled some of them." Bucky didn't seem to know where to look. The Virgin Mary? The Infant Jesus? "These others," Bucky stared at his knees. "I can't get to them. I mean, I could, but—"

"You'd get caught," Steve said, low and urgent. "Bucky, don't get caught."

Bucky looked at him with miserable eyes. "I don't want to get caught."

"Don't get caught," Steve said again, and then he was carefully ripping out the pages Bucky had indicated, folding them, tucking them into his jacket. "I'll take care of it; leave it to me," he said.

The words came out on a breath. "Thank you."

"Not necessary," Steve replied.

"There's more coming," Bucky said grimly. "I still don't remember most of it. I feel it like a sickness, like when you know you're going to throw up but you haven't. It comes back in pieces, big chunks all at once—sometimes in dreams. I wake up sick." He looked at Steve and his face changed. "Unless it's you," he said, mouth trembling. "Sometimes I wake up with a head full of you, and that's good. Those are the best days."

Steve's throat tightened and he looked away. "I wake up with you every morning," he said, and felt Bucky shift closer. They sat beside each other for a minute or two in companionable silence, listening to the faint echoes of other people's movements and watching dust motes spin in the air, and then Bucky said, softly, "Come on, let's go."

Outside, on the worn stone steps, Bucky turned up his collar and said, awkwardly, "So I work here now."

Steve couldn't help his start of surprise. "What, here? At the church?"

"Yeah," Bucky said. "They've got a shelter, and I was...I don't know, just doing odd jobs around the place, but then Father Leopold, he's the pastor, he sort of cornered me and insisted on paying me. And then he helped me find an apartment. It's not much, but—"

Bucky stopped and barked out a laugh, because Steve could hardly control himself: he was two steps from waving his hands around and doing a jig in the street. Bucky had an apartment! Bucky had an apartment in Baltimore! Baltimore was barely an hour away from DC! Maybe less if he—

Steve grabbed Bucky by the arms and grinned stupidly into his face. "That's great. That's just great, Buck."

Bucky looked cautiously happy. "I don't know how long it'll last," he warned Steve.

"Nothing lasts," Steve shot back, and Bucky couldn't argue with that.

Bucky's apartment was in the basement of a nearby row house, around the back through a weed-choked alley and down a couple of crumbling concrete steps. The paint on the white door was peeling, and both he and Bucky had to duck to pass through: inside, the low ceiling was only an inch or two above their heads. Cinderblock walls, a dingy black and white vinyl floor. There was a small bed covered with an army blanket in the corner, a battered table and two chairs. The kitchen was a metal sink and a hotplate, a small cube of a fridge—but there were two mugs on the counter. Bucky said, low and awkward, "You want coffee? I can make coffee," and Steve nodded wordlessly as Bucky turned on the hotplate and began to make coffee the way they used to, in a saucepan on the stove.

Steve took off his jacket and sat down in one of the chairs. There was a pile of old newspapers on the table, and Steve looked through them. The Baltimore Sun, but also papers in other languages. Russian. Polish. Ukrainian. Japanese—and it was weird to think of Bucky reading in Japanese, though of course Steve knew first hand that the serum made it easier to learn languages. He'd focused his attention on French and German back during the war, and he'd been working on Russian ever since discovering what happened to Bucky, though everyone said not to bother, considering all the translation tech they had now. But Bucky hadn't had translation technology, and this pile—Steve could feel the weight of decades in those papers; the long march of the Winter Soldier's years.

Bucky came to the table, a mug in each hand. He clunked Steve's coffee onto the front page of Czas Baltimorski before sliding into the opposite chair. Steve picked the mug up and sipped—and felt actually teary; it was overwhelming to be given coffee that tasted like coffee, doctored up just the way he liked it.

Bucky was staring at him. "I pictured this, you being here—" Steve nodded; there had been two mugs and two plates and two chairs. "—and now here you are."

Steve said, heartfelt, "Yeah. I pictured this, too," and then he laughed and set his mug down. "Well, no; I never pictured you making me coffee. I guess I must have a much—well, a much dirtier imagination than—" and before he could finish the thought, Bucky was up and dragging him out of his chair and kissing him, practically molesting him, clutching his head between his flesh and metal hands. Bucky shoved him backwards a little, and the back of Steve's legs hit the side of the bed and for a moment they clutched and danced awkwardly, still kissing, until suddenly their knees were bending and they were sort of folding together, going down, leaning back.

Bucky landed heavy on top of him. Steve smiled against his mouth and Bucky broke off the kiss and lifted his head. He said, panting, not so much looking at as looking through Steve, looking through Steve to the past, "Did you ever say—do I remember you saying—"

"What?" Steve asked; his cock was aching in his pants.

Bucky was lost, remembering. "You said..." He sat back on a bent leg and peered down at Steve, who was laid out beneath him, like he used to be: God, like he liked to be. "You said: 'I'm not fragile,'"—and oh, Christ, he had said that. He could remember saying that: could remember being small and horny and full of feelings and Bucky treating him with kid gloves all of a sudden, like fucking might break him where fighting hadn't, where his whole goddamned life hadn't. Steve remembered thinking that he had to set Bucky straight on this point and fast, and so he'd sucker punched him and knocked him back onto the bed at Furman Street and used his whole weight to keep him down, straddling him and pinning his arms with his knees and gripping his shoulders. And then he'd stared down into Bucky's crazy-handsome face, his forelock falling distractingly into his eyes, and said, low and forceful, "I'm not fragile, Buck." Bucky, flushed and warm and panting beneath him, had stared back up at him. Then he'd licked his lips and replied, roughly, "Prove it." So Steve had proved it. And then he had proved it again.

Now Bucky was on top of him, staring down, and so Steve scraped out, "Yeah, that was me," and he'd been hoping this would lead to some more rough and tumble fucking, but instead Bucky reached down to grab his backpack off the floor. The notebooks tumbled onto the bed, four of them: brown, blue, black, and hunter green. Steve recognized the brown one as the Hydra notebook, but Bucky tossed it and two of the others onto the milk crate nightstand. He clicked on a ballpoint with his thumb and opened the blue one on his thigh.

It opened to a picture of Steve—or no, to Captain America. It was the cover of the exhibition brochure, a cropped shot of him from the mural in the Smithsonian. Glossy brochures for the exhibit could be found in plastic cases all over Washington—his life was a major tourist attraction, a thing to do with the kids on a Sunday afternoon. I read about you in a museum, Bucky had said, but he hadn't been able to get the real story there. But he was maybe putting it together after all, because, as Bucky flipped to a clean page, Steve saw that the brochure and the pasted-in news clippings (research?) soon gave way to pages of Bucky's neat, tight writing: real memories, Steve hoped.

Bucky scribbled half a page of notes, then stared down what he'd written, gnawing at his lip, before looking up. "Sorry," he said. "Just I don't want to forget again," and Steve opened his mouth to say, you won't, but then didn't, because he couldn't. It felt like an empty promise; just words. What the hell did he know?

Bucky's gaze was moving up Steve's body, like he was trying to connect this memory—"I'm not fragile, Buck —to another one. "Did you," Bucky began, and there was a fleeting tension, a flicker in his cheek. "Did I? I mean, was it you who—" and Steve realized what Bucky was trying to ask him just as Bucky managed, "Did I used to like it?"

Steve's mouth went dry. "Yeah," he managed. "We both did. We both did it and we both liked it. I mean, we did a lot of things. We did—well, everything. Not all the time. We didn't—you know—not really at all in France. More in England." He stopped, swallowed, internally berating himself: Bucky was trying to build back his memories, Bucky didn't need him to be elliptical. "You found that cheap hotel near Euston and I would meet you there, do you remember? I forget what it's called." Bucky was looking at his body again, and so Steve went on, forcing himself to be explicit. "That was the only place we could actually—fuck. Other than that, it was catch as catch can."

"I don't remember," Bucky confessed. "But I want to do it," and Christ, two minutes ago Steve had been desperate for it, but—

Bucky's hands were on him, tugging his shirt out of his pants, reaching for the buttons. Steve shivered and tried to tamp his body down. "We should maybe go slower than this, though," he said.

"I don't want to go slower," Bucky said.

The words in his head twisted round and round, though he hadn't meant to say them. "But you don't remember."

Bucky frowned. "It was a long time ago," he said—but it wasn't, it was three years—No, it wasn't. Bucky had been awake and suffering while he'd been dead. "And it doesn't matter anyway," Bucky added, low and rough; he was opening Steve's jeans now, tugging at the fabric hard enough to lift Steve's hips off the bed. He dragged his underwear down, exposing him. "I want new memories," Bucky said, almost angrily. "I have memories but the ones I have—I want new ones. And the only good ones I have in my head are—" Bucky reached up, batted Steve's cheek, traced a fast orbit around his head. "—constellated around you, so." He took Steve's cock in his hand.

Everything stopped. They panted at each other. Steve was dizzy from trying not to thrust.

"I want to fuck you. Can I fuck you?" Bucky asked.

"Still not fragile," Steve said.

Sam pulled off his Falcon goggles, his face grimy from fighting. "Are you disappointed that he's not here?"

"No," Steve said, without thinking. In fact, he felt triumphant. The first Hydra nest on his list: routed, gutted. He and Sam had gone in like gangbusters, capturing not only Colonel Armand Yentz but a whole sleeper unit of commandos and an arsenal of guns, grenade launches, low level nukes and glowing blue Hydra weapons. The cops, army, and CIA were swarming all over the place now, putting the weapons into lead-lined armored cars and loading the men into supermax prison trucks. He couldn't wait to tell Bucky about—oh.

"I mean," Steve said slowly, noting Sam's sharp look, "I'm glad he's not here. You saw the vault. You saw the cryofreeze. He wouldn't go back to Hydra voluntarily, and if he hasn't been captured—then he's still in the wind."

"I guess, yeah," Sam said, and scratched at his neck. "I guess that's better."

"It is," Steve said, a little more sharply than he'd meant to. "Of course it is. He's not one of them, Sam."

"Okay," Sam said, but Steve knew when he was being placated.

"He remembered me, Sam. He knew me," Steve insisted, for what had to be the thousandth time.

Sam's expression was faintly amused but kind. "Hey, if he knew you and he pulled you out of the river anyway, I can only take that as a gesture of good faith." Steve made a face at him.

Steve drove up to Baltimore at odd times and parked his bike behind the crumbling shed in the unkempt back yard of Bucky's row house. Sometimes he met Bucky at St. Augustine's, slipping into their pew and waiting while Bucky finished mopping the vestibule, dunking his mop into the wheeled metal bucket, or cleaning trash out of the small church garden. Sometimes he went directly to Bucky's basement flat and knocked softly on the white door with its peeling paint. He tried not to draw attention to himself. Bucky wore jeans and old workshirts, a tattered jacket and a baseball cap, and so Steve tried to dress more or less the same, sometimes supplementing this getup with the clear-lensed glasses that Natasha had given him when they were on the run, because they made Bucky smile.

They fell back easily into habits from childhood, when they'd had no money—taking long walks and occasionally going to the pictures, playing cards and sitting around reading the papers, their heads in each other's laps. They had a lot of sex, because it was fun and it was free and it knitted them back together without talking. Bucky still didn't remember a lot of their old life together, and Steve wanted to fill in all the blank years they'd spent apart, to learn what had left Bucky so changed, but talking about it was hard. Their friendship had never been based on talking; they'd always seemed to know what the other was thinking. But that wasn't as true now, or maybe it was just that Bucky was thinking in languages that Steve didn't know. Some of them he couldn't even recognize.

In the end they came to terms over the notebooks. "The blue one's you," Bucky said without opening his eyes; he hadn't realized Bucky was awake. Steve had just been lying there in a post-coital stupor, savoring the moment, too happy to sleep, until his eyes found the notebooks. Then Bucky read his mind. "The brown one's them," Bucky murmured. "The green one's what happened to me. The black one's...what I did." Steve forced himself to relax, to settle back on the tiny bed, but Bucky went on, his eyes still closed: "You can look if you want. I've got no secrets from you. From myself, maybe," and Steve hadn't known which was the better part of valor, to look or not to look.

In the end, he sat up against the cinderblock wall and tugged the blue notebook out of the stack. Bucky rolled into his lap, taking advantage of the extra space, and went back to sleep, or seemed to, at least. Steve had been wrong: the picture of him from the Smithsonian wasn't pasted inside the cover, though it was very near the front. Instead, the notebook started with some random words scrawled in a shaky handwriting, Bucky's penmanship gone palsied.

"The BRIDGE," it said, and then: "was that the same man," and Bucky'd circled "the same man" so many times that the words were half blotted out. The word "WHEN?" was in a box, with an arrow drawn to "EARLIER" and then another pointed down to "ON ANOTHER ASSIGNMENT." On the next page was the first pasted newspaper clipping, Nick Fury's obituary. His own name appeared in the first paragraph, underlined—"...the D.C. apartment of STEVE ROGERS, otherwise known as ‘Captain America'..." It had been circled in red ink, and a line drawn to the opposite page, where Bucky'd written "Steve Rogers" and then "I met knew him."

Then there was a bulleted list of places and times that he'd seen Steve: on April 1 on the roof near Steve's apartment, April 3 on the bridge, April 4 on the Potomac. These were firmly and clearly written but after that there were dots, angry zig-zagging squiggles and then what almost seemed like another voice entirely -

White shirt.

Brown suspenders.

Wool pants with the holes darned

—and then Bucky'd circled the word darned and added a bunch of ????? and Steve smiled ruefully, because yeah, that was something that seemed to have dropped out of the world entirely. He'd could hardly even remember learning how to sew, it had happened so young, but his momma had worked for a living and he had only ever had two pairs of pants at one time, so if something happened you had to fix it: sew it, darn it, patch it carefully from the back. And something was always happening, particularly to his elbows or his knees, because when he was a kid he was falling and when he was older he was fighting, and Steve could remember it like it was yesterday, standing in the alley behind the drugstore and muttering "goddammit" under his breath because the bleeding cut above his eye would heal but the way his shirt was ripped, the way the guy'd grabbed it and pulled—well, that was going to take some serious sewing, and it was never going to look right even still. Momma was going to pitch a fit.

Bucky'd drawn a line up to the top of the page, back to that frantically circled phrase—"the same man?"— and the urgency in the question was such that even though this had been written months ago, Steve blindly palmed a pen off the nightstand and wrote, beneath: "Yes, that was me. I was small. I had holes in my clothes but I tried to mend them," and then Steve hesitated and added, "You always said it looked like tweed. You were nice to me," and then he made himself turn the page, and go on.

STEVE ROGERS, it said, and below that: CAPTAIN AMERICA, and the next bunch of pages were all scrawled notes about Captain America: the familiar boring rehash from the papers or the internet, Wikipedia, though Bucky'd circled words he'd been interested in: Brooklyn. 4F. Super serum. SSR. Howling Commandos. Valkyrie. Crash. Ice. Steve frowned and began to page forward through the notebook—it occurred to him that he hadn't yet seen Bucky's own name anywhere. It didn't appear until pretty far down in Bucky's Captain America summary, and even then there was no suggestive circling, underlining, or doodling. "Sgt. James Buchanan Barnes KIA 6 days before crash," Bucky had written, with no apparent recognition that he was writing his own name.

Steve clicked the ballpoint again. The writing was denser here, but there was space at the side. Steve circled Bucky's name and then drew a line out to the margin. "This was you," he wrote in small letters, and then: "I wanted to die," and then he was slamming the notebook shut and almost pushing it back onto the milk crate, because a guy could get lost in the endless white space between Bucky's fragmented memories—but Bucky was back, Bucky was right here.

"Hey, look," Sam said awkwardly, "I gotta ask you something." Sam was sitting, hunched over, on the edge of his bed, his fingers laced together—Sam always took the bed near the window when they shared a hotel room, which they sometimes did when they were looking for—well. When they were out pretending to look for Bucky.

Steve had just come out of the shower, and was dressed in loose sweats, his hair damp. They hadn't found Bucky—well, of course they hadn't—but he and Sam had taken down yet another Hydra stronghold. Bucky continued to supply them with good leads as he remembered them—and that intel was worth something, wasn't it? That was real work, important work, even if the chase for Bucky was... "Sure, Sam," Steve said casually. "Of course."

"This friend of yours," Sam said, looking up at him, meeting his eyes. "Barnes," and then he was shaking his head and smiling ruefully. "Man, this would be so much easier if we could just have a drink or something—"

"Hey, we can have a drink," Steve pointed out. "I won't get drunk, but—"

"Well, I won't get drunk either," Sam said, eyeing him, mock offended. "Not on one, anyway," and so they cracked open the minibar and popped the tops off two bottles of beer. "All right," Sam said, after they'd clinked and drank; the beer was surprisingly good, though not quite cold enough. "This friend of yours: Bucky. I know you were kids together. I read the books, I went to school—I know you saved him, I know you served with him. And I know what that means: what war does to you, how it bonds you together. Riley—it was like losing a part of me, an arm or a leg," and Steve held Sam's eyes and nodded, because he knew: he understood what Sam had been through.

Sam was turning his beer bottle around and around in his hands. "So I get that he'd mean a lot to you, even without the whole thing of him being, like—the only other native to have survived from your home planet," and when Steve laughed unexpectedly, Sam smiled and went on, glibly: "Like I get that you're Kal-El and he's Jor-El, or—"

"He's not Jor-El!" Steve spoke Superman.

"—whatever, Bucky-El," Sam said, rolling his eyes. "Or whoever else survived."

"Nobody else survived," Steve said.

"Yes, they did." Sam counted on his fingers. "The girl—Supergirl—and there was also a dog."

"What dog?" Steve asked, but Sam seemed to realize that he'd strayed from his point, and shook his head.

"What I'm saying," Sam said, trying to drag the conversation back on track, "is that I get it: there's a million reasons you've got to find this guy, but..." and suddenly Steve understood what Sam was asking, and then Sam saw him understand and flushed, and abruptly switched gears: "No, sorry, forget it."

"No, it's all right," Steve said distantly.

"Just it feels like there's more," Sam said.

Steve's throat was tight. "There is more."

"It's none of my damn—" Sam said. "But I just, I wondered. If you and him were—you know. If you were—"

His face got hot. "—sweethearts, yeah," Steve admitted, and he saw from Sam's expression that that wasn't the word he'd been thinking of, and then Sam pulled a rueful face at him and said, on a huffed-out laugh, "Sweethearts, sure. That's what my momma would have said, too. That's nice, I like that."

Steve's face felt even hotter. "What—I mean, what would you call it now?"

"I don't know: boyfriends, maybe?" Sam suggested. "Lovers? Partners?"

"That's nice," Steve sighed. "In my day, it was fruits, pansies, poofs. We just said friend." He asked Sam, curiously, "How did you guess?"

"I didn't guess," Sam admitted. "It was something Natasha—You know how she was always trying to set you up, pushing Sharon at you, and that other cutie, Janine." Steve blinked; he had no idea who Janine was. "Janine," Sam repeated. "She's always there when you turn in your mission reports. Black, pixie hair. Looks a little like Rihanna. Janine," and oh yeah, that pretty girl up at the Head Office; chic, with a nice smile. But Sam was rolling his eyes with obvious, theatrical frustration: "A-ny-way Natasha seems to have given up trying to introduce you to womankind, so I was trying to work out why. Natasha isn't a quitter, but she seems to think you're off the market," and Steve felt a sudden twinge. Did she know? What if she knew? Did she know he'd found Bucky already?

He realized that somewhere, deep down, he'd been debating taking Sam into his confidence—Sam don't be mad at me, but I found him already; he's in Baltimore and I'm kind of seeing him a couple of times a month–but suddenly knew that he wouldn't—couldn't—risk it. "Maybe Natasha can do something for you," Steve said, meaning that maybe Natasha would introduce Sam to Janine or Sharon or Lillian from Accounting, but when Sam blushed, Steve abruptly realized that Sam was—wow, sure, of course; obviously—pretty damn interested in Natasha.

Sam admitted it with an awkward smile. "She already does, man," he said, and that was a perfect change of subject.

He'd resented the Smithsonian retrospective, the way it had reduced his life to a couple of props and some red, white, and blue bunting. But now, working his way through Bucky's blue notebook, he was grateful for it—because it had put Bucky right at the heart of the exhibit, on a wall ten-foot high, etched in glass. And the Smithsonian had commissioned a twenty-foot mural, whose artist had painted Bucky like a romantic hero and put him at Steve's side. This was where Bucky had first seen himself; that was how Bucky had first seen himself. Steve wanted to hug whoever'd curated the damn thing: they had asked him to speak at the opening, and he'd turned them down, but if he survived this, if he and Bucky survived this, he'd go back and offer to do them a goddamned public Q&A.

The blue notebook was bookmarked to a picture of Steve, but later in the pages, Bucky had pasted in a small picture of his own face, cut from the mural; the size of a mug shot, like he was a suspect. Barnes, James Buchanan aka "Bucky." Born—1917? 1918? Historians apparently debated this—there was some irregularity with Bucky's birth certificate—but Steve knew it was 1917 and so added the note—March 10, 1917—just in case Bucky'd forgotten.

The past came back to Bucky in bits over the pages—lists, glimpses—and his handwriting grew stronger and more recognizable. Three sisters, green dresses, red hair ribbons; laughing. Amy, Grace, and Roberta—and Steve's pen hesitated over the last name, because Becca had been Bucky's favorite, the apple of his eye—and would it hurt him more to know that he'd forgotten her name or to let it stand uncorrected? Steve bit this lip and fixed it—Rebecca, you called her Becca—and turned the page, where it said: He is on the fire escape with a white cat.

Steve stared, transported—yes, that was right; that was true. Momma had forbidden him the kitten—she was convinced cats carried diphtheria and was unwilling to risk Steve's health to prove otherwise—but he had adored the kitten and so had sneakily built a bed for it on the fire escape under the overhang. The cat had come back to him more or less faithfully, and used to let him pick it up by the scruff of the neck and scratch under its chin while Bucky watched them both, smoking: Momma wouldn't let Bucky smoke inside the house either, because of his asthma.

Steve wrote in the margin, her name was Snowball, Momma wouldn't let me bring her inside so I kept her on the fire escape. That gave him an idea, and he turned to a clean page and began to write:

I don't remember when I met you. We have been friends for damn near forever. But I'm pretty sure I fell in love with you that time I got beat up behind Greenwald's in (?) 1932 I guess. You broke up the fight but then you told me I was a sorry excuse for a fighter and that I should have kept my hands up to protect my stupid face, and then you made me go with you to the Boys Club and punch the heavy bag over and over. This was ridiculous because my arms were like noodles, but you showed me how and you made me practice. You were the only one who ever said get up, keep going, be better—you and my ma. And later—I don't know if you remember –but the first time you kissed me, you told me my face was still stupid but you didn't want anybody punching me and making it worse than it—

Steve jerked the pen up, sick before he knew why—then remembered Bucky bent over him, holding him down and punching him in the face with his metal fist. Horror had dawned on Bucky's face. Maybe that was why—

Steve snapped the notebook shut and stared at the blue cover. It had a grainy pattern in the card he'd never noticed before. He flipped it open again and paged to where he'd been. He had to finish his thought, finish the story—

There was new writing at the front. Beneath where Steve had written, I had holes in my clothes but I tried to mend them, Bucky had scrawled. You'd be all the rage now. It's me who'd look corny in my plaid suits and hats.

"What the hell is the matter with you?" Sam demanded, when Steve opened his apartment door. "Don't you ever look at your damn phone?" though actually, Steve had gotten a lot better at remembering to check his phone, because Bucky had taken to texting him from inexplicable numbers, always different, soon disconnected. Coded requests to meet, or sometimes pictures: the Quaker Oats box, a packet of Lucky Strikes, Bugs Bunny. Once it was a grainy video file, 1 minute 39 seconds. Steve saved it to his phone and watched it over and over, knowing that Bucky was doing the same. A man awkwardly working his way down a ladder. Buzz Aldrin on the moon.

"Sorry Sam." Steve yanked the door open wide. "Come on in—"

"No, you grab your coat and come out," Sam said. "I'm illegally parked round the corner—but I've got a lead." He waggled his eyebrows, looking pleased. "On our missing person. An old friend of mine," Sam went on, "runs the VA in Baltimore. Says he might have seen your boy," and Steve said, "Oh," and "That's great," and went to get his coat like a zombie. On the way out he grabbed his phone, glanced at the screen. A bunch of texts and notifications, most of them from Sam. Missed Call. I'm outside now. Missed Call. I'm coming over. Missed Call. Missed Call. Come on pick up your damn phone. I've got a lead on your friend. Missed Call. Hey, call me.

And in between that, a nonsense string of text from an unfamiliar number: UMCUEEATRMEULEIUASEEATRL. Steve shoved the phone into his pocket, pulled the door closed and followed Sam down the stairs. Anagrams on Friday—he'd gotten good at all the codes and ciphers he and Bucky'd used to use when they were kids: codes and Russian had become his second languages. COME TO CHURCH USUAL TIME. It wasn't until they were in the car, Sam driving them north toward 95, that Steve was able to slip the phone of his pocket and text back, LIE LOW, as Sam said pleasantly, eyes on the road, "It's only about an hour away. Be great if we found him, wouldn't it?"

"Yeah," Steve said, his eyes on his phone. There was no answer, but neither was it Message Failed To Send.

"I sent his description out to some people I know. Veteran's Services," and then Sam cut his eyes at Steve and added, his voice going serious, "Not his name or who he is. Nothing about James Barnes or the Winter Soldier." Sam looked back to the road. "Just that they should keep their eyes open for a vet I was looking for. About thirty. Long dark hair, blue eyes. Russian as a first or second language, with a high-tech prosthetic arm." There was acid in Steve's throat, and he swallowed and pushed the button to lower the window for some air. "It ain't as unusual a description as you'd think," Sam said, sighing. "VA's full of people like that. Which is why," and here Sam glanced between Steve and the road, "I thought it was worth taking a shot. I figured: if you're right and I'm wrong, if he's still the man you say he was, then he's a guy who's just been cut loose from the army, a guy who just lost that structure, you know? That numbness, that certainty—one foot in front of the other, you know what I'm saying?" Steve nodded, "and he's maybe taking stock for the first time in a long time." Sam stared at the road. "A long damn time. And he's maybe feeling the same pain as the rest of us. He'll maybe do what we all do—get angry or drunk or high—and then maybe he'll look for help. Find the VA." Sam looked at Steve again. "If he's who you say he is."

"He is," Steve scraped out, because Bucky hadn't just gone to the VA; he'd gone back to church.

He was tense enough over the ride that Sam reached out to grip his arm once or twice, saying, with all kindness, "We're gonna find him; we will," even as that was exactly what he feared. He thought he might actually rip the armrest off the door handle. He could see his knuckles going white, his fingers pressing down, down into the leather—and then they were going past Bucky's exit and on into East Baltimore.

They pulled off the highway into a grim huddle of brownstones and vacant lots. Sam drove through the cracked, treeless streets, eventually pulling up in front of the Jefferson Community Center, a low brick building with painted metal doors. They got out, slammed the car doors, crossed the street. Inside there was a double-doored foyer, and beyond that was a dimly lit corridor with various doors leading off; it looked like what Steve remembered of school.

As Sam approached an office with a glass window, a man with tight gray curls and a wide smile came out to greet him, hands extended. They shook and then hugged, slapping each other on the back, and then Sam said, "Steve, I want you to meet Lamont Taylor. Lamont, this is Steve Rogers: Captain America. I pretend to be cool about that."

Lamont laughed and reached out to shake Steve's hand. "Pleased to meet you, Cap. It's a real honor."

Steve smiled helplessly as he shook it. "Same. And I'm sorry: you say Lamont, I think Cranston, I can't help it..."

Lamont looked surprised. "Yeah, that's what he said. The guy," he said, turning to Sam, "that you're asking about," and it was all Steve could do to keep the sudden sick feeling off his face, even as Sam shot him a triumphant grin.

"Is he here?" Sam asked.

Lamont shook his head. "No, but he was. He didn't stay long, he— Do you want to come in?" he said abruptly, gesturing back toward his office. "Sit down? I got a coffee machine," but Steve didn't think he could survive scrutiny right this second, so he interjected, "Can you give me a tour first? I'd love to see the place."

"Sure," Lamont said proudly, and most of the story came out as they walked. "This is the shelter," and the room reminded Steve of nothing so much as the triage centers he'd seen during the war: field hospitals set up in ballrooms, in barns, in churches. It was crammed with metal cots, all empty. "It's a requirement they get out during the day so we can clean the place," Lamont said. "We've got a job hall, a game room, a gym—or there's a church down the block, a library, a couple of places that'll let you do laundry for free if you show them your sleep ticket. He did that, the guy you're looking for," Lamont told them. "Came in, spent the night, washed himself and everything else, then took off. I wouldn't have remembered him if you hadn't asked; he was real low-key, that dude," and Steve just bet he was; Bucky was professionally invisible. "But he was white," Lamont said, "which made him unusual around here," and Steve understood then why Bucky'd set up camp on the outskirts of Central Baltimore, with its huge Polish and Russian populations, "and then there was that thing about The Shadow—who the hell knows about that?"

"I don't even know about that," Sam said, looking from Lamont to Steve.

"Lamont Cranston," Steve explained. "He was The Shadow's secret identity. It was on the radio when I was a kid."

"Yeah, but that was like a hundred years ago," Lamont said. "No offense, Cap."

"Not quite that long," Steve said.

"Long enough that there were still white people called Lamont," Lamont told Sam, who grinned. "Come on back to the office," Lamont said, and there he made copies of the paperwork Bucky'd filled in at check-in: Alexei Orlov, Specialist, 4th Infantry Division, and it didn't even look like Bucky's handwriting. But he'd seen documents and mail in Bucky's apartment, passports made out to Alexei, Mikhail, Dmitri. He didn't think that Bucky's Russian identity was entirely an act, either, because sometimes when Bucky woke up in the morning, he spoke Russian before he spoke English. Sometimes Steve tried to respond in kind, though Bucky smiled mockingly at his accent.

Steve looked up to see Lamont looking at him. "So," Steve said awkwardly, "you haven't seen him since?"

"I barely saw him then, to be honest," Lamont admitted, and then, giving into his curiosity: "Who is he, Cap?"

Steve saw Sam press his lips together; it was up to him to decide how to answer this. "He's—a soldier, a member of my team, gone AWOL," Steve said, and saw that Sam was nodding, slowly, at the truth of that. "I don't blame him for running," he added quickly. "He was—poorly treated. But I want to find him. I want to make it up to him."

"Well, he was here six months ago," Lamont said. "He's probably still in the system somewhere; they usually are."

"We can run his name, run everything on his paperwork," Sam suggested. "See if he's used this info any place else. It might triangulate into something interesting. It gives us a place to start, anyway," Sam finished optimistically.

"Yeah," Steve said. "That's great, thanks."

"You're disappointed," Sam said, on the way back.

"I'm not," Steve protested. "I mean, I am. But I'm—you know, okay. I'm fine."

"Uh-huh." Sam was focused on the road. "You're fine; you're always fine. But you know, I look at your face and I think that part of you doesn't want us to find him. Is maybe scared that we'll find him. And that's legit, you know?" Sam sent him a look of grim sympathy. "That is a legit way to feel under this particular set of circumstances."

Steve didn't reply.

Sam dropped him back at his apartment at half past eight in the evening. By twenty to nine, Steve was on his bike, roaring back up the highway toward Baltimore. The coded text on his phone said MESSAGE RECEIVED.

He parked his bike in a dark corner of the dilapidated back yard and went to knock on the door to Bucky's basement apartment. There was no answer, and there was no answer, and then nervously, Steve used the keys Bucky had given him, and went inside. It was empty, and worse yet, it had a kind of abandoned feeling, which he couldn't explain until he realized that the notebooks were missing. For a moment he just stood there, heart pounding, and then he went back out into the night and fast-walked the couple of blocks to St. Augustine's, hands jammed in his pockets.

The church was dark, but Steve stuck to his gut and ran up the steps and yanked at the heavy wood door. It was open. Steve stepped into the foyer, and then went into the church, which was lit only by the thick candles in the niches and a small lantern near the tabernacle. Bucky was sitting in their usual pew, his backpack beside him on the bench.

He looked up as Steve approached. "Are you alone?" he asked quietly.

"Yeah," Steve said, and then the implications settled on him; did he think Steve would turn him in?

"Tell me everything," Bucky said, and Steve answered immediately.

"Sam put out of a description of you to veterans' services. You rang the cherries in East Baltimore—the Jefferson Community Center," he said, and Bucky nodded. "Bucky," Steve added hesitantly. "Maybe it's time to come in."

"No," Bucky said.

Steve sat down beside him on the pew, the backpack between them; he'd had a worse thought. "Please don't go."

"I'm not going," Bucky said, which surprised him. "Not yet, anyway."

"But..." Steve sat there for a moment, breathing hard and staring down at his hands, torn between what he wanted for himself and what he wanted for Bucky. Finally he gritted his teeth and said, against interest, "Buck, they'll be looking for you. They've got you spotted two exits from here—just a couple of miles—"

"Yeah, and if I were a burglar I'd be really worried. Good thing I'm an international assassin," Bucky said, and then he went on, almost kindly, "They're going to be looking for me in concentric circles, radiating out of here and gradated over time. I know the search protocols—Hydra's, I mean. SHIELD's too but it's not SHIELD I'm worried about here. It's Hydra I don't want following me, but the last place anyone's gonna look for me now is here."

"You did it on purpose," Steve said slowly. "You went to a shelter two neighborhoods over before you came here."

"Within the search perimeter, yeah," Bucky said. "I'll be safe here for a while longer, I guess."

Steve's arms and legs felt like rubber. But. "Bucky, I'm worried. I don't know how this ends," he said.

"Me neither, pal," Bucky replied. "But I don't think it's going to end how we expect."

Bucky locked up the church, and they went back to Bucky's basement apartment, and they were in each other's arms the minute the battered door closed behind them, Steve pushing Bucky against the wall in the narrow corridor and kissing him, dragging his lips and tongue all over his face, his thumbs stroking the rough beard along Bucky's cheeks.

It took him a moment to realize that he was hearing more than the sound of his own blood in his ears. "S'alright," Bucky was whispering to him. "S'alright, it's all right," except it wasn't, and Steve pressed his face hard against Bucky's prickled cheeks and gritted out, "I'm afraid you're gonna disappear again. I'm so afraid."

"Well I might," Bucky said, which wasn't the answer he wanted, "but if I do, I'll find you, swear to God. Never had trouble finding you: you're wherever the trouble is. And so long as you're wearing the outfit, you're hard to mi—"

The word died as Steve slid down to his knees, dragging his hands down over Bucky's body, over his scarred chest, his flat stomach—to the waistband of his pants. Steve tugged his shirt out, then opened his button and unzipped his fly. Bucky was already hard, pushing up against the thin fabric of his underwear. Steve bent to nuzzle him with his lips and his nose before pushing his hands up underneath Bucky's shirt, wanting to touch warm skin. The scarring—Christ, it made him angry, would always make him angry; he didn't see how he was ever going to get over it. He rubbed his hands over Bucky's chest, nipples catching against his palms. His fingertips bumped the ridges of Bucky's ribs as he pulled his hands out—and then he was dragging Bucky's underwear down, gripping his cock and pulling it into his mouth. "Fuck," Bucky said, and then his hand was in Steve's hair. He was tugging and trying not to tug, rubbing his fingers around in crazy circles. It made Steve gulp, hold his breath, and then Bucky's hand tightened and they found the right rhythm. And then Steve closed his eyes and really went for it, greedy and unashamed—like he'd done when they were kids, and he'd had to convince Bucky that this was an okay thing, like he'd done during the most desperate hours of the war. Holding Buck's hips like this, worshipping him with his mouth, Steve was transported back to all the shower stalls and locked closets: little boxes of stolen privacy. Bucky's metal hand touched his face, warm and surprisingly gentle, though Bucky was usually self-conscious about it and kept it gloved or tucked in a pocket or pressed against Steve's back when they were making love. Unless he couldn't help himself, like now, and Bucky hips begin to jerk as his breaths went ragged. He was trying not to thrust but Steve blindly dug his fingers into Bucky's hips and tugged him forward and back, rocking him into his mouth and—

"Oh, fuck," Bucky said, making helpless fists in Steve's hair. "Motherfucker," and then he was groaning and trying to pull out even as he was coming, but Steve slammed him back against the wall and held on, sucking until his mouth was flooded and he choked and then turning, coughing and spitting, dragging his arm against his mouth.

He was still getting his breath when Bucky grabbed him by the arm and dragged him up and over to the bed. Bucky gave him a push and Steve sprawled backwards, flopping, and let Bucky open his pants: like the old days, just like the old days, when everything was terrible and still somehow so, so much better than now.

The next threat came from an unexpected quarter.