Scenes From A Marriage: Hazy Days of Winter

by Speranza

Author's Note:This is the 4 Minute Window Advent calendar for 2017 (can you believe it?) As always, my goal is to do a bit of the story every day (knock wood) between the Immaculate Conception and Christmas. Explicit eventually, the rest as it comes. Feel free to send me your hopes and dreams if there's something you want to see in this 'verse and I'll do what I can (if it fits and makes sense). Hope you enjoy: buckle up! LATE BREAKING NEWS: Bonus!!- this series will feature art by the magnificent Alby Mangroves!

"Maybe they packed it wrong," Steve said finally, frowning down at it.

"They didn't pack it wrong," Bucky muttered, studying the schematics. "It matches the picture, just - it doesn't make any damn sense."

Elbows braced on the edge of the workbench, Steve stared down the mechanism. It had been delivered from their supplier in an innocuous-enough looking box, but now that the parts were spread across the workbench it looked to have about a thousand pieces, none of which seemed to belong to the same machine: there were pipes, valves, electrical and telephone cables, strange looking plastic containers. A computerized interface was supposed to run the thing, but there were no buttons on it, nothing labelled in any way. The bare bulb hanging over them cast shadows on the machinery, laid out before them like an autopsy. But the client had requested it specifically: given them the model number and everything.

"I don't want to do any more new construction," Steve said, rubbing one eye beneath his glasses. "Let's just stick to restoration."

Bucky glanced up. "That's strangely negative of you."

"Buck, I hotwired a plane that was less complicated than this," Steve said.

"Pal, the year before I escaped from Hydra, they sent me to the Gobi desert to find a crashed alien spacecraft, which I repaired and flew back to Siberia, and that was less complicated than this," and then Bucky pushed away the specs, sat back on his stool, and sighed. "Okay, don't laugh, but I'm gonna make a couple of guesses about this thing."

"I'm not laughing," Steve said gravely.

"Okay, well, first of all - I think it's a shower ," Bucky said dubiously, and Steve rolled his eyes.

"Yeah, I know it's a shower," Steve said, and when Bucky made a face at him, he added, "You've obviously never showered at Tony's. Nine nozzles, water coming at you every which way: it's like being attacked. And this," Steve pointed, "is like a robot to set the temperature, and this thing here changes the pressure, and this is, I don't know, probably a phone and a radio or something. But I don't know what this is," he said, pointing at another smooth black box of electrical components, "or this," the thing looked like a bagpipe, "and I'm damned if I know what these little plastic reservoirs are for."

"Well." Bucky picked up the schematics again. "If I'm reading this right and I haven't lost what's left of my mind, they're supposed to spray vitamins on you. Like vitamin C or something."

They looked at each other, then stared down at the machine.

"I don't want to do anymore new construction," Steve groaned. "Let's just stick to—"

Bucky's phone rang. They held each other's eyes even as Bucky wormed it out of his pocket.

"Yeah?" Bucky said guardedly, and then: "Yeah. Right away," and then he was sliding off the stool and saying, "I gotta—"

"Yeah, go; go," Steve said quickly. "I'll figure this—" but Bucky was already halfway to the wooden staircase. Then Steve heard himself call, "Buck?" without really even meaning to.

Bucky halted mid-flight. His head jerked 'round. "Yeah? What?"

But Steve was paralyzed, conflicted; the words died in his mouth. "Nothing, sorry," he said hastily. "You go on," and Bucky bolted up the wooden steps and into their apartment, and when he came down a minute later he was wearing black pants and a tac vest and moving with the Winter Soldier's grim sureness. He lifted a glossy black helmet from the back of their motorcycle and put it on, then pulled on a pair of goggles, obscuring his eyes. Steve quickly consulted the handheld computer Tony'd given them - "All clear" - and then held the small side door open so Bucky could wheel the motorcycle out quietly before roaring off into the Brooklyn night.

Clint was waiting for him on a rooftop in East New York; he was crouched down on the edge of the cornice and staring down the back of the building into the yard on the other side. Bucky went over silently and stared down, too. The area behind the buildings was dark and eerily quiet. All the streetlights were broken, and there was no light in any of the buildings. But there was seething movement. Bucky tapped the goggles Tony'd given him and the lenses changed, sharpening his night vision. People, lots of them, crowded toward a narrow doorway, silently shoving themselves forward. The crush of them spread, fanlike, across the cracked concrete.

"What the hell is this?" Bucky murmured. "Drugs? Zombies?"

"You tell me," Clint said darkly. "It's been days like this: at least three days I've been watching, anyway. Yesterday I tried to get in closer, see what was going on. Figured I'd ask an old lady," and Bucky nodded: he'd already noticed that the crowd was all ages: men, women, even a few kids. Hawkeye tugged at the sleeve above his left gauntlet; his arm was wrapped in a white bandage. "She bit me," he told Bucky. "Hard! Seventy years old if she was a day!"

Bucky gaped as Clint tugged his sleeve down again. "What did you do?" he asked.

"What did I do? I got a tetanus shot! I called for backup! I called you!" Clint said in mock-outrage, and then: "No, but she was clearly out of her mind, was the thing. Her eyes were all strange. I'm not gonna beat the shit out of an old lady who's out of her mind—I mean, they all are," Clint said, waving a gloved hand down at the backyard, "look at them. That's what makes this so complicated. And okay, I think we can take them, but we might be hurting a lot of innocent people and I'm not even sure for what."

Bucky turned his attention back to the people below. A few more had managed to cram themselves inside, though now they were stuck there: they looked to him like bees more than anything, swarming. His eyes searched the building's facade for another way in, but there wasn't one: the windows were covered with metal shutters, the whole building locked down tight.

"Maybe this ain't a case for us at all," Bucky suggested doubtfully. "Maybe we ought to call—you know, the mission. Social services, whatever you call 'em now. Or maybe we should just call the cops."

"Yeah, I thought about that; we could do that," Clint replied. "Except—you know, an old lady bit me. And after she did, a couple of the others started to look my way—and there was a weird kind of electricity there, Barnes: something contagious. They weren't like a mob exactly; they were more like a pack ." He looked at Bucky and said: "You ever get chased by coyotes?"

Bucky looked at him. "I grew up on Atlantic Avenue," he said, pointing. "Not a lot of coyotes."

"Yeah, well, there are coyotes in Iowa," Clint said, "where I grew up and—"

"I'm sorry to hear it," Bucky said, shuddering a little. "Coyotes, Iowa, the whole thing."

"—so I recognize the—look, Brooklyn's not the only place in the world, you know."

"Yeah it is, though," Bucky said, and Clint opened his mouth to argue, then obviously thought better of it. He put the argument aside with a visible effort.

"Okay, so I'd like to know what the hell is making the fine citizens of Brooklyn act like a pack of coyotes," Clint said pointedly. "And I'd like to know before I get anyone else involved, because the cops are gonna escalate the situation, and the social workers might get literally chewed up."

"Well," Bucky said, shrugging, "I got a metal arm, let ‘em try biting that," and Clint nodded and said: "Yeah, that's what I was gonna suggest: you and me go in together, playing defensive ball, and maybe we can hold them off long enough to see what the hell's going on in there. Maybe it's just a rave or something," Clint said, sighing. "Maybe Springsteen's playing in there."

"Maybe," Bucky said noncommittally; he didn't know what a rave was, or a Springsteen, but neither of them sounded very likely. He checked his protective gear and put the safeties on all his weapons but one; he didn't want old instincts kicking in if the targets were citizens.

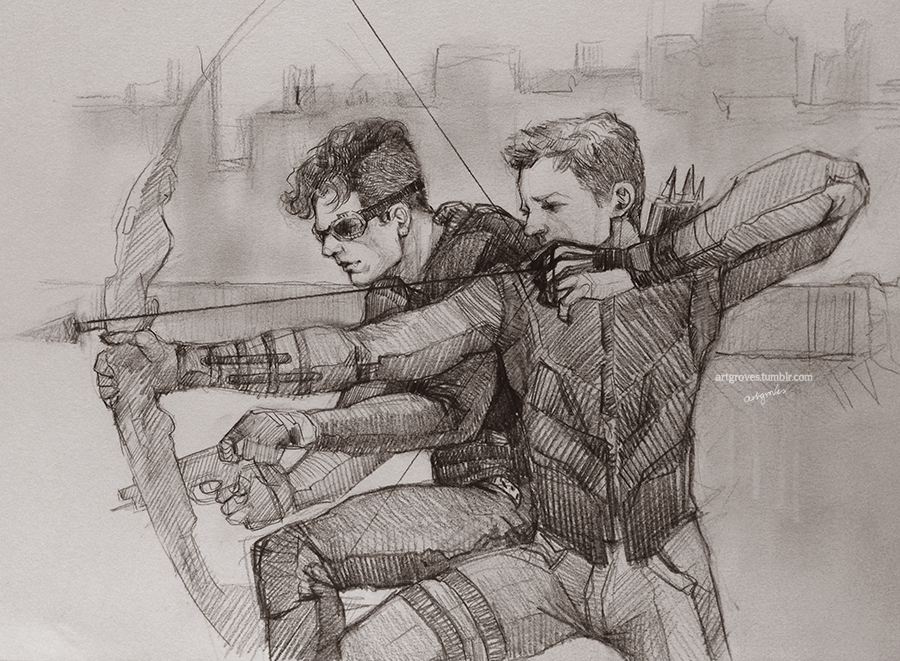

Hawkeye did the same, then pulled the bow off his back in a smooth motion and fitted an arrow to it. There was a cable attached, and he aimed at the roof across the way. Bucky immediately got the plan: Barton meant for them to drop down on the people below like spiders, right at the doorway. Surprise would go a long way, and then speed: if they moved fast, they could clear out a circle. Work back-to-back, fling people away, and get inside. Escape would be the hard part.

"Let's go," Bucky said.

Figuring out the schematics of the shower kept his mind off things for a while, and then he had to integrate it with the architectural layout of the bathroom, and then he had a good half-an-hour of righteous rage at the softness and bloodyminded wastefulness of people— who the hell needed Vitamin C sprayed on them? Already they lived in paradise: all the hot water you could want!—and that got him through walking the dogs and making himself a Dagwood sandwich.

He was sitting in front of his empty plate blankly picking the label off his bottle of beer when the thought forced itself on him, fully formed: I should have gone with him. He'd wanted to...except he didn't want to, not really; not when push came to shove. He'd nearly said it—"Buck, hang on, I'll come with you,"— but then he'd imagined the reality of it: stars and stripes, helmet, shield.

Being Captain America. Again. And sitting there in his warm apartment full of real things, the home Bucky had made for them, that they'd made together by living and loving there, the last thing on earth he wanted was to—

Gracie nudged at his leg, put her head on his knee, and Steve grabbed her face in his hands, and roughly stroked the fur back away from her eyes, her mouth. She wagged her tail a couple of times and then turned around twice and ducked under the table, where she sprawled over his boots. Steve smiled and felt suddenly better; Gracie was the nervous type and sometimes needed a little extra reassurance, but she was more than willing to return the favor. Good dog.

Still, unpleasant thoughts nudged at the back of his mind, and he itched to paint. But it was too late and too dark, so he dragged over a sketchpad and fished a nub of pencil out of the pocket of his corduroy pants. He drew without thinking, sketching blindly, just losing himself in shapes and textures, random associations. Images tumbled out one after another: one curved line became the flare of a skirt (his mother's), another the front end of the trolley, and then there was the zigzagging staircase outside—the tenement where his mother had died, Christ, that had been awful. Steve stared, in his mind's eye seeing Bucky climbing the stairs in his dark suit—

He hastily turned to a clean page. Now, as then, he escaped to the pictures: nothing like the dull, half-empty box where they sometimes saw movies now, but the old Loew's palace on Flatbush, bigger than a church and more impressive. He could remember how it felt to watch a movie with four thousand other people: that's what made it a movie, as far as he was concerned. Curved banques of seats appeared at end of his pencil; enormous spiral columns. He drew Veronica Lake and absently lettered the poster of This Gun For Hire , the last movie they'd seen before—

He moved his pencil and drew the newsstand next to the BMT on Flatbush Avenue. The newsstand wasn't there anymore; neither was the station; neither was the elevated BMT, for that matter. In fact—the thought was upon him now—nothing he'd drawn was here anymore; it was all from before. He frowned down at the pages, turning them: his mind had given him 1938, 1941, 1942. He hadn't thought about the past in a while; his life had got traction again. But he was thinking about it now, because...

He pushed the scrapbook aside. He had to go to bed. He ought to, anyway. He'd likely be on his own tomorrow, installing that stupid shower system. He turned on the radio while he washed his dish and rinsed out his beer bottle. The NPR host was interviewing a novelist, so there hadn't been a bombing or a fire or an alien attack: that was good. Steve switched off the radio and took the dogs down to their doghouses. Then he brushed his teeth and put on his pajamas.

He turned down the heat and switched off the light. He had just pulled back the heavy wool blanket when the compulsion became unbearable, and he groaned and went to the foot of the bed. The metal trunk was padlocked, but Steve felt around for the secret compartment they'd carved into the heavy wooden bedpost and palmed the key. The locker was half-empty—Bucky'd taken his tac vest and equipment; his knives and guns—but the Captain America uniform was there. And the helmet. And—

Steve lifted the shield. The street light reflected off the vibranium.

He stared at it for a long time, then carefully shut the lid, set the lock, and got into bed.

Sleep didn't come. He tossed and turned, tried everything he knew from when he was a kid including two decades of the rosary, and was just debating a glass of warm milk when he heard the metal door open downstairs. Steve quickly put on a bathrobe and slippers and went to the stove: he wanted to be in the middle of something when Bucky walked in.

The milk wasn't yet warm when Bucky came upstairs. Steve glanced over as the door opened to ask Bucky if he wanted a glass—and then stopped. Bucky was banged up and bleeding, his pants ripped and his hair disheveled. There were jagged scratches on his face and neck—and Bucky laughed wryly at Steve's shocked expression, grinning at him through his bloody mouth.

Steve switched off the gas. "Jesus, what the hell happened?" He was used to thinking of Bucky as damn near indestructible: he couldn't see how Bucky'd let anything get in so close.

Bucky sat down hard at the kitchen table. "You ever hear of Bruce Springsteen?"

"You were attacked by Bruce Springsteen? " Steve gasped.

"No, as it turns out," Bucky said, and then he was covering his battered face with a gloved hand and laughing—almost giggling. Steve began to laugh, too; Bucky's mood was contagious, even if Steve knew it was mostly about coming down off the agitation of fighting. Steve got the first aid kit out of the cupboard and, bypassing the milk, brought over a bottle of whiskey and a glass.

He sat down and poured out a couple of fingers. "You look," Steve pushed the whisky over; Bucky took it gratefully and downed it, "like you were attacked by...cats," he concluded, deciding that was about right. "Like maybe ten thousand angry cats."

Bucky shoved the glass back toward Steve who immediately refilled it and shoved it back. "You're not far off," he said, taking a smaller sip this time, and Steve saw that there were threads of blood circling in the whiskey when Bucky put the glass down again. Steve frowned and opened the latch of their first aid kit, pulling out a bottle of antiseptic and some gauze.

"What was it about?" Steve asked curiously, upturning the antiseptic against the gauze, and Bucky sat back in his chair, tugged off his gloves, and reached into the velcro pocket of his tac vest. He came out with a little glass vial held between his finger and thumb. Steve leaned forward curiously: whatever stuff that was inside—it looked kind of like a powder, or maybe a crystallized paste—it was electric green and glowing. "What the hell is it?" Steve breathed.

"The fuck if I know," Bucky replied, peering at the vial a little wonderingly. "Whatever it is, though, it turns people's brains to mush. I saw it happen myself: practically a whole neighborhood gone cuckoo—eating this stuff. Taking it like communion, crawling over each other to get to it. Barton says..." He trailed off, shook his head like he couldn't believe what he was going to say, and then said it. "He thinks it's alien, some kind of chemical we just can't handle. I took a bit of it as evidence just because we don't trust anybody, especially the lying sack of shit that is the CIA," and Steve tightened his jaw and nodded. "Barton's gonna bring some of it to Tony, too, get him to analyze it, and maybe to SHIELD, if they've got their heads on straight this week." Bucky shook his head and put the vial carefully down. "What a strange goddamned night, pal."

"Sounds it," Steve said, and then: "Here." He extend the pad of soaked gauze. "Take this."

"Fuck that," Bucky said, a little hoarsely, and then he was reaching past the antiseptic to brush the back of his fingers against Steve's bearded cheek. "It's funny," he said, almost absently, "but I can still see you in there sometimes."

"I told you, I'll shave it if you don't like it," Steve said softly.

"I don't mean that," Bucky said; he was fixated on Steve's face. "I mean the old you, from before," and Steve felt a stab of desire, so familiar to him from the days when Bucky had been so much older and taller and more handsome and yet inexplicably willing to make love with him, even though he was visibly fighting it, even though ambivalence had been in every line of his face. It hadn't occurred to Steve that Bucky's ambivalence was on his account—that he thought he was corrupting Steve into a life of sickness, or sin. No, Steve had gone with a much simpler explanation; he'd just assumed that Bucky already knew he could do better than a sickly alley cat like Steve. "Some girl's gonna make a play for you," Bucky would whisper when they were in bed together. "And when she does, you just tell me, okay?"—which had left Steve with a gut-clench of anxiety, waiting to hear that Bucky'd found himself a girl. But Steve wasn't ever what you'd call a quitter, so he'd done the only thing he could think of: he'd made love to Bucky with enough focused intensity to keep his mind off anyone else.

Everything he knew of sex he'd learned through Bucky—Christ, he remembered the first time that Bucky had blown him, once they'd gone past the boys-will-be-boys stage of things. It had been such an unexpected, overwhelming pleasure in a world where those were rare—but every pleasure he learned he tried to give back in spades. Steve grinned, remembering how Bucky'd liked it when Steve sat in his lap and kissed him all dirty, and when Bucky grinned back through his cracked and bloody mouth, Steve knew he was remembering it, too.

"I'd do it but I'll break the chair," Steve warned.

"So what? We fix things," Bucky replied thickly, and then he was tugging Steve out of his chair and over to him. Steve went, trying to keep his weight light, but when he settled himself across Bucky's thighs, straddling him, the sturdy wooden chair creaked but held. Steve exhaled and settled down, carefully cupping Bucky's scratched face. "See? Craftsmanship," Bucky scraped out, tilting his head back, and Steve kissed his mouth greedily, licking and sucking his bruised lips, tasting blood. He ground down in Bucky's lap, making him groan—and Steve was instantly hard in his thin pajama pants.

Beneath him, Bucky was hard, too, which—Christ, that was exciting. In the old days, he would get Bucky to come like this: sitting in his lap, kissing and teasing him with his hips, letting him thrust up and rock against him until he shuddered and lost control. God, Bucky had loved that. And that had been enough for Bucky, back in those more innocent days; Bucky'd been happy with that—but Steve, wanting devotion, wanting to keep him, had egged him on, pushing further. "C'mon, " he'd whispered, "you can," coaxing Bucky to rub himself against him, skin to skin; coaxing Bucky to slip his cock between the press of Steve's thighs. And things had escalated from there, half-by-accident, half-on-purpose, because it hadn't taken Steve long after realizing Bucky liked boys to determine that he was gonna be that boy—

Steve's mouth moved against Bucky's. "C'mon," he whispered, "you can—" and Bucky grabbed him under his thighs and lifted him, all two hundred pounds of him, onto the kitchen table. Bucky pushed him back and mouthed his way down Steve's belly where his pajamas had ridden up, before opening his fly with a quick tug. The striped bottoms were held together by four tiny snaps.

"Aw, jeez," Steve gasped, forever getting more than he bargained for—Bucky's warm breath and the tickling tease of his hair before Bucky's pulled him in, lips sliding over him. "Oh, jeez, Buck, I—oh," and Bucky had to use his metal arm to hold him down, because Steve was panting and wild, chest heaving—and Bucky kept slowing down, mouthing and licking, driving him crazy. Steve's fingers dug into Bucky's hair, tugging probably hard enough to hurt, though Bucky didn't seem to mind or even hardly to notice. Steve came in a sudden, hard surrender, his body just giving up, and Bucky gagged a bit and slid off, gasping, and worked him through it with his hand, which was dripping. Pinpricks of light danced in Steve's vision; he was wrecked.

"I'm not done," Bucky scraped out, dragging Steve up, half-dizzy, from the table and towing him toward the bedroom—and oh, fuck, it turned out he really wasn't.

Steve fell into a deep sleep afterwards, though he woke up three times, twice with Bucky sprawled in his arms and once with his arms empty and Bucky leaning naked against the headboard and smoking a cigarette. Bucky didn't smoke often and almost never in public (since he couldn't exactly explain about being a supersoldier and that this, out of everything, wasn't gonna be what killed him), but he liked to have one after sex, sometimes. Steve snuggled back into the warm, rumpled sheets and then rolled to curl against Bucky's bare thigh and hip.

The tobacco didn't smell as sweet as it did in his memory, but he liked it anyway; it reminded him of home. He closed his eyes. Bucky's hand dropped into his hair. Steve sighed contentedly.

"I couldn't get out of my head last night," Steve said, though the moment the words were out, he realized that Bucky knew all about it already: Bucky had taken him to bed to fuck it out of him.

"Yeah," Bucky said, "I saw the sketchbook." He took a deep drag and then said, on the exhale: "You should hit something, you'll feel better."

"No, it wasn't like that. I just thought...maybe I should've gone with you," Steve said.

That seemed to take Bucky by surprise. "Why? It wasn't anything. There was already two of us being beaten up by little old ladies, we didn't need you there," and that made Steve laugh.

"Okay, well, that makes me feel better. But...I don't know, when you were doing it, I didn't need to think about it. Being..." Steve stumbled on it; it was hard to say out loud. "...Captain America."

"Oh, I see," Bucky said softly. "Yeah. A thing like that, it doesn't stay in a drawer."

Steve draped an arm over his eyes. "Yeah. And...I don't know how I feel about it. It's...I don't know."

"It's called anger, that feeling," Bucky said.

"No, it's...at least, I don't think it..." —and now it was Bucky who was laughing; Bucky was laughing out loud.

"Yeah, you don't think; not a bit," Bucky said, sitting up and stubbing out his cigarette in the ashtray. "That's anger, buddy; you're so fuckin' angry, you don't even know it," and now that Bucky'd said it, Steve could feel it: he was choking on it, shaking with it; smothering in it.

"Breathe, Steve," Bucky said calmly, and stroked his hand up over Steve's forehead, and Steve felt suddenly like he could take the whole world apart with his bare hands: just tear it down brick by brick. Bucky said, meditatively, "I'm not particularly angry myself, temperamentally."

"No," Steve managed, "you're not," which was true: Bucky'd always been a charmer - a real sweetheart, everyone said. Which only made what happened to him so much fucking worse—

Bucky looked down at him and said: "Seriously: you gotta hit stuff. Just for your own peace of mind," and then he thought for a moment. "Let's you and me go for a drive this weekend," he said. "We'll go out in the country; see a tree or a lake or something. Change of scene."

"Yeah, okay," Steve said, and swallowed.

"Steve, you don't have to be Captain America if you don't want to," Bucky said.

"Well, I don't want to," Steve said.

"Then fucking Q, fucking E, fucking D," Bucky said.

They only got through installing four of the nine shower nozzles by Friday, and there were wires hanging everywhere and the tile had only just arrived: forty boxes of it. Bucky looked tense and a little hopeless, and Steve felt it, too: there still so much to do, and it was just a bathroom, ferchrissake.

"I don't know, should we work the weekend?" Bucky asked finally.

"Work the weekend?" Steve repeated in his most self-righteous voice. "People died, Buck."

Bucky laughed, then showed him a shit-eating grin. "Right you are, pal," and so it was that they set out to drive over the Brooklyn Bridge, first thing in the morning.

They'd taken a couple of day trips out of the city, sometimes riding together on Steve's motorcycle, sometimes driving the Studebaker now that Bucky'd gotten it running. Mostly they'd gone upstate, to Bear Mountain and the lakes and orchards there, but they also drove up into New England and once, down the Jersey shore, to the fun festival that was Asbury Park.

Mostly they liked to drive without a particular destination, just taking local roads instead of the big highways and stopping at whatever seemed interesting; a dairy farm, a fruit stand, a local luncheonette. It was soothing to Steve just to sit there and watch the countryside roll by out the window: this country they'd fought for. He liked to lose himself in the rhythm of Bucky's aimless driving—except, Steve thought, as Bucky flicked the turn signal for the third time in ten minutes, Bucky's driving on this trip seemed rather less aimless than usual.

Steve looked over at him. "Are we going somewhere special?" Bucky didn't reply.

Ten minutes after crossing into Pennsylvania, Bucky turned onto a narrow lane of rough road and the back of Steve's neck prickled: this was familiar, he had been here before. "Buck, is this—" Steve began, but he didn't need to finish the question, because there was the old gas station up ahead: two abandoned pumps and and three bays. Bucky turned the Studebaker onto the gravel drive and pulled to a stop. "Hang on," he said, and got out. Something lurched in Steve's stomach as Bucky went to the center bay, unlocked the peeling garage door, and sent it rattling up on its chain. Then Bucky came back and slowly drove the Studebaker inside.

He recognized it immediately, the garage—it was the first place they'd come to after Stark Tower, after the escape through Grand Central and the old Biltmore hotel. Steve felt like had been born from the trunk of the black cab Bucky'd driven that day: happy birthday to me. But there was no cab here now, though they'd left it that day. The whole place seemed emptier than Steve remembered, too; in his memory there'd been loads of tools on the walls and machine parts scattered across the benches.

Steve got out and shut the car door, the slam echoing through the garage. Bucky followed, then leaned against the car door and watched him. Steve wandered, taking everything in: he recognized the grimy window, the bare tree branches outside. At the back was the tiny john where he'd dyed his hair; splotches of brown still stained the basin.

Steve turned back to Bucky, finally; Bucky was wearing the intense stare of the Winter Soldier.

"What happened to the people who owned this place?" Steve asked.

"They retired. Florida, I think." Bucky didn't volunteer more. But Steve didn't need more.

"So how many places like this have we got?" Steve asked.

Bucky bit his lip and thought it over. "A couple. Six? Seven. I don't like to be cornered," and then he was lurching away from the car and coming over to Steve, gripping his arms, and that was familiar, too. "And I don't want you ever to feel cornered," Bucky said, and then they were hugging each other hard, hands knotting in the backs of each other's jackets and squeezing tight. Steve held on, breathing in the smell of him, the solidity; he didn't want to let go.

"Where would we live," Steve muttered into his ear, "if we lived here?"

"In town. Somewhere," Bucky replied. "No shortage of places." He gave Steve a last, hard squeeze and stepped back. "It's a nice town, too—coal, back in the day. They used to dig it out of the mountain, take it by steam train down to the canals, then float it over to New York City. All gone now, of course," he said. "There's a town square, a city hall—and a bunch of houses standing empty, take your pick. Always room for guys willing to make themselves useful—"

"—who know how to fix things," Steve said, nodding. "Yeah. How's the food?"

"Surprisingly not terrible," Bucky replied. "German," he added, shrugging; Steve shrugged back: that war was over, "but you could do worse. You can get a sausage or a schnitzel or a nice roast beef sandwich."

Steve's stomach rumbled. "I would love a nice roast beef sandwich," he said, and they got back into the car.

His phone rang halfway through their meal at Otto's; he and Steve exchanged wary looks before Bucky answered it, cautiously. "Yeah?"

"Hey, you brought me alien drugs, which—you know, ten years too late, but it's the thought that counts."

Steve watched him, chewing; Bucky made a face and rolled his eyes. "I can't talk now."

"You can't talk? Because it sure sounds like you're talking. I mean, I'm pretty sure I just heard you. Though I sometimes hear voices. Not usually yours, though. Nothing personal. Tell you what: just tap once for yes and twice for—"

Bucky groaned, slouched back, rubbed his eyes. "All right, already; okay."

"Okay, then. Look, I shared my info with those bastards at SHIELD, but they're freezing me out, and Barton's asleep in a dumpster somewhere, so I figured I'd go straight to the horse's mouth."

"I'm not a horse," Bucky said. Across from him, Steve shrugged and went back to his sandwich.

"No, that's true, very true: can't put one over on you. When you and Barton went into that building, did you happen to notice if there were black marks on the walls? Like scorch marks—except for no sign of fire?"

Bucky sat up; sharpening. "Yeah, there were," he said, and Tony made a satisfied noise. "Why?"

"Because I don't think this was our first alien drive-by," Tony said grimly. "JARVIS found two similar cases in the police record: different goop, same marks. The goop wasn't as potent, though: NYPD wrote it up as an unspecified contamination the first time; gave the landlord a ticket. The second case they wrote up as a case of environmental poisoning: two people hospitalized."

Bucky opened his mouth to ask a question, then stopped: the waitress was coming over to refill their coffee mugs. He smiled at her and waited until she drifted off. "So what do you think?"

"What do I think? I think someone's testing a goddamned biological weapon on us," Tony said.

Bucky sighed; there was nothing easy in this life. "Okay," he said.

"I'm gonna set up some sensors to track any unusual heat signatures in the city," Tony told him, and okay, that was smart. "Meanwhile, stay alert: everybody be ready to assemble."

"Yeah, okay," Bucky said and hung up. Steve raised his eyebrows inquiringly.

"What was that about?" he asked, and Bucky shrugged and made himself smile.

"Nothing," he said. "You know: just the usual."

They took a walk around town after lunch; it was cold, and people were mostly huddled inside, which was perfect: they didn't want to draw any attention to themselves. They walked through the center of town - the park with its memorial to the veterans of the Civil War, past the town hall and the library, a row of six different Protestant churches - and then out toward the periphery. It didn't take long - the whole place was smaller than their neighborhood - and they were just about to turn back when Steve pinched a bit of Bucky's leather jacket and pointed. Bucky looked: on the outskirts of town there was a building with a ton of junk cluttered out front.

Bucky couldn't see what the hell they'd want there but Steve was already loping toward it, and as they got closer Bucky saw what had captured his attention. The yard was full of crazy things: street signs and bits of masonry and a claw-foot bathtub and a cast-iron pot-bellied stove. There was a beautiful old pedestal sink that just needed a little cleaning up; it would go perfectly in the Reynolds townhouse, which they were going to fix up once they finished the nightmare they were working on now. Beautiful curves, and Bucky bet he could get it for cheap. Steve was examining the pot-bellied stove. "I like this," Steve said finally. "You like it?"

"For who?" Bucky asked.

"For us!" Steve replied. "It'd be nice to have," and then he was standing up and peering at the building, which was so jammed with stuff that you could hardly see where to get in. There was a hand-painted sign over the door: BEST PICKS ON ROUTE 6. "Think they're open?"

"Let's see," and honestly, it was like walking into a deathtrap: one wrong move and you could be buried alive. The place was enormous, but piled so high with stuff that you had to be a cat, practically, to make your way through the narrow passages between the junk. There was so much stuff that Bucky couldn't see what he was looking at. And then things fell into place, and he said, without meaning to, "Oh." Beside him Steve had gone still; eyes very wide.

It was like...a giant had picked up a Brooklyn tenement from the their time and shaken it out like a cereal box. It was like every piece of crap from their past had been picked up and carried here: old chairs and tables and pots and pans, a battered Magic Chef stove and oven that had been cutting edge in the 1930s, and now looked like it was from the prairie. There were piles of old cameras and heavy black telephones and enormous radios, even a Victrola, with its crank and enormous horn. There was a whole wall displaying fancy dishes and glasses, including some gold-etched plates that looked just like a set his grandma used to have and never used. Bucky felt Steve's hand on his arm and turned, his throat tightening: there was an enormous pile of battered helmets from their war, like the guys had just thrown them into a heap; leather bags and boots and old mess kits. A shoebox full of random medals, the bronze gone dull, the ribbons faded and old.

Bucky turned to Steve in alarm, but Steve looked okay: a little glassy, maybe, but okay. "Well, this gives you a sense of perspective," Steve said finally. "I guess this is where everybody ends up: with all your stuff in a pile somewhere. You and me, we just lived long enough to see it."

He ought to shut up, but the words wanted out. "If you weren't alive, I wouldn't want to be."

"I know," Steve said. "Me neither," and then: "It's the one piece of good luck we had."

The sun went down early these days. They drove back through the darkness toward the glowing orange smear of light, and then suddenly they could see it, the glowing constellations of stars in the shape of buildings, outrageous and magnificent. Steve's throat tightened with love for it; New York City. "It won't work, you know," he said around the lump in his throat. "We're doomed."

Bucky glanced across the car, then smiled into the darkness. "Since 1934," he agreed.

Steve rolled his eyes. "Not that. I mean—"

"I know what you mean."

"I mean, I appreciate that you got us safehouses all over the country—"

"—and out of it," Bucky said, and when Steve glared at him, he shrugged. "Can't be too careful."

"I guess not. But..." Steve gestured toward the glittering city. "Just look at it, Buck. It's the mothership."

"Yeah, it's pretty; I'll give you that. Bright lights and everything. But we have hardly any coyotes," Bucky said, like he was Clarence Darrow summing up for the jury. "Clint says that Iowa has tons of coyotes. They come right up to the house, " and Steve sputtered and nearly choked on his own spit before he managed, "Is that good? Is that supposed to be something we want? "

"I don't know, I wasn't really listening," Bucky admitted. "He seemed proud of it? I think?"

"Well. It takes all kinds, I guess," Steve said.

There were Christmas lights and glowing snowflakes strung up across some of the avenues, and when they turned into the CIDC driveway, Steve watched the enormous garage door roll up and felt grateful to be back, to be home. "Hey," he said, once Bucky had turned off the Studebaker's engine, "why don't we go out and get a Christmas tree?"

Bucky's eyebrows flew up. "What, now ?"

"Yeah, now," Steve said. "It's not that late. There were some guys selling them down the block; I saw them."

Bucky slouched back and squinted at him. "You mean, you don't want to do that thing where you say ‘Let's not do Christmas,' and I pretend to go along with you until you change your mind and then we run out and get a tree at the eleventh hour? Because I've got to tell you, pretending to go along with your nonsense is what makes it feel like the holidays. Now it doesn't feel like Christmas."

Steve groaned, though he supposed he deserved it. "Let's just go get the damn tree," he said.

The stand was two blocks down, around the corner from Holy Innocents. Bucky cast his eye over the lot and then, wordlessly, handed cash to one of the guys and pointed. "It's a little big, isn't it?" Steve hazarded, as the guys wrapped the tree in netting to make it easier to carry.

Bucky's mouth curled up at the corner. "A little big is the perfect size. I don't believe in good taste when it comes to Christmas trees."

Steve laughed and pulled his hat down against the cold and took one end of it; Bucky took the other, and together they hauled it back to CIDC and up the wooden stairs to their apartment.

"Okay, it's big," Bucky said, panting, once they'd flung the door open and wrestled it in; it lay across their apartment floor like an enormous bear.

"No, it's great," Steve said, pulling his hat off and wiping sweat from his brow. "It's gonna be like living in a forest. Maybe the coyotes will come," and somehow they managed to get the tree upright and (mostly) contained in one area, though they had to shove all the furniture around.

Steve was in the kitchen putting together some celebratory hot toddies when the lights went off. Steve turned: the enormous tree was covered with fireflies of warm yellow light; it looked like a skyscraper with all its windows lit. Bucky stood there, staring at the tree in wonder, and Steve put down the mugs, and went over, and kissed him, impulsively, cupping and turning his face.

Sunday morning, Steve got out of bed quietly and slipped across the landing to the studio to paint; there was so little light now, he had to make the most of it. He'd been working in oils, just putting thick layers of paint down, half sculpting with it, but after their day at BEST PICKS ON ROUTE 6 he wanted to paint what he'd seen. He dragged the brush, then his fingers, through the layers of thick impasto, mixing the olives and ochres right on the canvas, making one rough curve after another until the dark green helmets piled up before his eyes. He mixed some white, then picked up his knife and began to slash light onto the helmets, making reflections, trying to give them some dimensionality and shape—

It was the smell of bacon that finally caught his attention; he turned and Bucky was standing there in his pajama pants holding a plate of scrambled eggs with ketchup and bacon. He was staring at the picture Steve was painting. "That's good," he said absently. "I like that," and then, blinking: "I thought you'd want breakfast. There's coffee up, too," and Steve abruptly realized he was ravenous. Starving, and—he reached for the plate—totally covered in paint. He looked despairingly around for a rag, then debated just wiping his hands on his clothes—and then Bucky smirked, held up a strip of bacon, and fed it to him. It tasted like paradise. He ate it straight from Bucky's fingers and then the licked the grease and salt from his lips.

Bucky was looking a little...glassy. "Oh, well... " he said, low and throaty, and fed Steve some more bacon and a couple of spoons of scrambled egg. After he'd fed Steve the last piece of bacon, Bucky leaned in to kiss him quick. "Mmm," Bucky said, licking Steve's lips and then his own, "delicious,"—and seriously, Steve was only human at that, and he reached out and slid his hands onto Bucky's skin just above the rise of his pajama pants, leaving streaks of green-black paint on his hips. Bucky shuddered hard, his tiny brown nipples tightening, and Steve detoured to give each one a hard suck as he sank to his knees, his hands moving up Bucky's muscled torso and leaving trails there too. "Oh jeez," Bucky said as Steve tugged down his pajamas pants and took him into his mouth, and then Steve closed his eyes and went to it, his hands grasping for Bucky's hips, thumbs stroking down along the base of his cock.

It didn't take long, because Bucky was shaky on his feet, his hands sliding over Steve's head, grabbing and trying not to grab his hair, fucking and trying not to fuck his mouth—and so Steve worked intently to send him over, hands grasping to hold him steady even as he let out a low whine and rose up on his toes and—Jesus, there he goes. He gentled and sucked Bucky through it, loving the trembling flutter under his tongue and all the little aftershocks.

Finally Steve let Bucky slip out of his mouth. He nosed Bucky's thick thatch of pubic hair and gave his softening cock a quick kiss before sitting back on his heels and wiping his mouth with the back of his— He laughed, because now that was a work of art: the whole middle of Bucky's body was covered with streaks of paint and olive-green fingerprints. He smiled up at Bucky, a little wonderingly: God, what a painting he would make. He wanted to paint him just like this.

But first things first: he was so hard he could barely breathe. "Buck," he managed, "you—wouldn't want to—"

"Let's go," Bucky said, hauling him up and dragging him back across the hall, and Steve bent him over the bed and pushed into him slowly, gasping and fighting for self-control. He rocked gently, his hands sliding up from Bucky's hips to his strong shoulders, bending to kiss the scars around the metal plates. Bucky was making a soft, incoherent, keening sound and convulsing around him, and Steve's composure began to slip. "Oh, Steve," Bucky breathed, "Steve," and he couldn't help it, he was gasping like an animal, hips stuttering, shoving forward until they were both shouting out loud, and thank God, really, that the walls were solid and they had no near neighbors, because Jesus H. Christ. Steve came, moaning, nearly blind with it, and collapsed across Bucky's back; beneath him, Bucky was fighting for breath, hands knotted in the sheets.

"Okay, well..." Steve muttered, but Bucky'd already drifted off, and Steve followed, almost helplessly. When he next opened his eyes the light had changed, and Bucky'd wedged in close and was softly snoring into Steve's armpit. He was covered in paint - smudges on his arm, his back, his cheek; he was a picture, and Steve was going to make a painting of him. But first...

He disentangled himself and went to wash, and when he came back to get dressed, Bucky lifted his head and looked at him muzzily. "Whatcha doing?" he asked.

"I've got to go out for a bit," Steve told him. "But I'll be back as soon as I can." He went to the old trunk at the foot of their bed, and Bucky's attention sharpened; he pushed up in their rumpled sheets, frowning, to watch. Steve pulled out the shield and slid it into the old black cymbal case he used as a carrying case. "I know what to do, Buck," Steve said. "At least, I think I do."

Bucky looked at him for a long moment, and then said, "All right, Steve. I'll be here," and Steve went over and kissed him with rough intensity, meaning it as a promise; a holy vow.

"There's turpentine on the shelf in the studio," Steve said, as a parting shot.

"Yeah, and fuck you," Bucky said, and looked down at himself with a sigh.

He walked a couple of blocks and got onto the Manhattan-bound train, finding a seat in the corner and tucking the bag holding his shield between his construction boots. Because it was a Sunday, there were fewer trains and so it got really crowded once they crossed into Manhattan, though he liked being in the thick of people: it felt normal and human and familiar.

He got off in the chaos of Times Square and fought his way onto the shuttle. On the other side, he pushed through the turnstile, walked into the station—and stopped. "Uh, excuse me?" an irritated woman said from behind him, and Steve muttered a quick apology and got moving again, walking fast until he was standing in the Grand Concourse near the clock. Then he stopped to take it all in: the enormous departure and arrival boards, the people rushing in every direction, the enormous windows and constellations of stars overhead. Smiling to himself, he took the curved staircase down to the dining concourse and got on line at Whole Bean Coffee, where he bought himself a chai latte with a shot that cost six dollars and eighty four cents, the hell.

Still, it was hot and delicious and he wandered around the station, taking in the other food stalls—pretzels, hot dogs, the ice cream stand near the doors for Tracks 125-126. There weren't any homeless veterans or street kids or other beggars sitting around the station today; they'd been moved on, Steve thought, a little bitterly, because it was the holidays. Now there was a brass band dressed in red jackets and Santa hats playing Christmas music at one end of the hall, and that was pleasant enough if you didn't stop to worry about what had happened to the homeless veterans, the street kids, and the beggars.

The thought made him feel heavy inside, and he finished his latte and chucked the cup into the garbage. Then he trudged back upstairs, the cymbal bag slung over his shoulder. The main floor of the station was where all the fancy shops were—expensive handbags, expensive computers, expensive wallets and lipstick and perfumes, NOW 50-70% OFF, LAST MINUTE SALE, STOP IN AND SEE OUR CHRISTMAS DEALS, HURRY BEFORE IT'S TOO LATE—and Steve walked past them up the corridor and into Stark Tower.

He pressed the button to call the elevator and waited. Only the bottom two floors of Stark Tower were open to the public, and he was the public now, he supposed, so he should probably go and announce himself to the concierge. He stepped into the elevator and was about to press the button for the lobby when JARVIS said, "CAPTAIN ROGERS, HOW NICE TO SEE YOU," and Steve smiled and craned his neck, looking for the camera—he'd always felt it was more polite to "look" at JARVIS, though Tony never did, and of course Jarvis didn't really have a face to look at.

"Hello, JARVIS, nice to see you too," Steve replied. "Hey, is it possible I could go up to my old room? That is, if it wouldn't bother—" The elevator shot up. Steve's stomach lurched a little, and then his ears popped: it had been a while since he'd been in an elevator like this.

"YOU MAY OF COURSE VISIT YOUR ROOM," JARVIS said. "IT IS STILL YOUR ROOM."

The elevator stopped, doors opening to discharge him onto his floor. Steve hesitated, then walked down the hall toward what had been his suite of rooms. He opened the door and—IT IS STILL YOUR ROOM, Jarvis had said, but Steve hadn't realized that it had been kept exactly as he left it. He stared: his favorite sheets were still on the bed, and all the stuff from his Washington apartment was there: books on the bookshelf, his phonograph and records, the framed army posters and pictures of the Howling Commandos. Sketches he'd done of Peggy, and Bucky, and his mother. Steve had left that day with only the clothes on his back, but the rest were in the closet, including a pair of broken-in motorcycle boots that he'd never quite been able to replace. Steve had a thought then, and went to flip through the shelf of records: Benny Goodman, The Andrews Sisters, Henry James, The Beatles, Radiohead, Elvis Presley, Elvis Costello (he'd bought the wrong one, the first time) Marvin Gaye, Nirvana, Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Best Hits of the ‘50s, Saturday Night Fever—oh, there it was. He yanked it out and studied it. Bruce Springsteen. He'd have to bring this to—

The door behind him opened and Tony burst in, looking disheveled; he was wearing some kind of headset with wires trailing from it, and he seemed to be holding part of an arc welder. Steve turned and they blinked at each other.

"JARVIS said you were here," Tony said.

"Yeah," Steve replied awkwardly. "I'm here," and there, on the wall next to where Tony was standing, was the hook where he'd once hung his shield; where he hoped to hang it again. He swallowed and said, "You, uh...wouldn't happen to have any of that really good whiskey left?"

"Cancel everything," Tony said, and it took Steve a moment to realize he was talking to JARVIS. "The whole day; put everything on hold. Come with me," Tony said, and that last part was to him.

They were three glasses into Howard's good scotch when Steve hefted the black cymbal case up onto the bar and shoved it at Tony. "Here," he said. "I brought this for you. I was going to leave it for you, back when I left, but..." His throat tightened. At the last minute he hadn't been able to do it, and he had taken the shield and the uniform with him.

Tony unzipped the curved bag part way and peered inside to confirm that it was what he suspected it was. Then he zipped it up again like he was afraid of it. Maybe he should be.

"It should be yours," Steve said. "You should have it."

Tony bit his lip and gave a long, slow shake of his head. "Cap, " he began, and it was unnerving to hear that kind of uncertainty in his voice: near to just plain wrong. "I don't think—"

"Your father made that shield, Tony. Hell, your father made me— "

"No, he did not, " Tony said, with sudden, surprising vehemence. "No. Some things I know and—"

"Then let me tell you something you don't know," Steve said, cutting him off. "I'll tell you something nobody knows, not even Bucky."

That got Tony's attention; his eyes were practically black. "Tell me," he said.

Steve poured himself another glass of Howard's very fine whisky, and drained it; it seemed to warm his insides. He'd committed himself to talking. Now he had to figure out where to start.

"I have been here before," Steve began finally. "In fact, some part of me feels like this is how it should be, like this is the normal way of things: Bucky out there, being a hero, while I stay home, drawing pictures and pulling my little red wagon." Tony was miming almost theatrical confusion, but Steve was determined to make him understand. "I'm telling you the truth, Tony: this is who we are—or who we were back before Project Rebirth and your dad and Zola and everything that happened to us. I'm trying to tell you something real—are you listening?" and Tony opened his mouth, then decided not to interrupt and just jerked a nod; yes, he was listening. Good.

But this was the hard part; the part he hadn't ever told anybody. Steve took a deep breath and just let it out all in one go: "When they took me for Project Rebirth, I figured they were just looking for a guinea pig," he said. "Do you understand? I mean, I figured that had to be why they wanted me, sick as I was, instead of one of the big guys, healthy," and there was a shocked comprehension dawning on Tony's face: good, he'd got it. Steve nodded rapidly. "I figured it would just kill me—and that was all right, because plenty of guys were laying down their lives for their country and I was willing to do it, too, and that was about the only way I was going to get to do it. When they put me into the machine, the only thing I was thinking was that I wished I'd had the guts to ask Peggy to kiss me, cause you know: getting kissed by a girl, it was kind of a thing back then. But it wasn't that important in the scheme of things..."

Steve trailed off, rubbing his chin thoughtfully; in his mind he was there, in the underground lab, with all those worried faces around him, and Peggy's sad, sad eyes. It had been like being put to death, just like the stories he'd read in the papers about the electric chair—except he was going to be being killed for doing the right thing, not the wrong one. That hadn't surprised him; it was what his mother had always said anyway, and the war just proved it.

Tony had emotion thick on his face—he had no poker face at all—and Steve said, quickly, to give him cover, "So, you can imagine how fucking shocked I was, literally and figuratively," and the use of bad language seemed to put Tony back on an even keel. "I never thought it was going to work —I thought I was just Test Subject Number Three."

"You weren't wrong," Tony managed; he sounded a little strangled but mostly okay. "I mean, it's basically never worked before or since. What happened to you was like being struck—"

Tony stopped; he'd gotten into trouble again, and Steve hastily stepped in to rescue him. "—like being struck by lightning; yeah, it was a lot like that," Steve said with a wry smile. "And then I came out..." he spread his hands and looked down at himself, "like this. And nobody knew what to do with me. I mean, I didn't even know what to do with me. Tony, my first shield? It was just a sheet of metal. It was a prop. I took it with me to Austria because it was better than nothing, but—you know, I just hit people with it. It wasn't smart. And then..." He touched the black bag with his fingertips. "Your father gave me this and made me bulletproof."

He seemed to have run out of things to say. Tony picked up the bottle of scotch and refilled both their glasses with a sad shake of his head. "You know, it's funny," he said. "My whole life, I was angry that Dad gave you the shield and not me. I wondered why he never asked me to pick up something like that; I never thought about how hard it would be to put down." He sat back and looked at Steve. "But I got over it; I got past it and made my own way. I'm Iron Man, baby. I can't go back now." He took a drink and said, "I'm sorry, Steve. But that shield's not for me."

It was snowing a little by the time he got off the train in Brooklyn, and he trudged back to Coney Island Avenue with the flakes stinging his face. Their block all was locked down on a Sunday night—the stores all shuttered, the metal garage doors rolled down—but the windows above Coney Island Design & Construction were glowing with warm yellow light. Steve stopped to look up at it, the snow blowing around his head, and suddenly didn't mind the weather much at all.

He heard the thump of the drums the minute he entered the garage. Bucky had the phonograph turned up so high that it sounded like there was actually a band playing up there, but that was one of the benefits of living in an industrial building, and Bucky liked to take advantage of it now and then. Steve tried to make out the song: The Modernaires, it sounded like. Hi Diddlee I Di.

He climbed the steps and found Shop Cat on the landing. She looked aggravated; their apartment door had some hell of a nerve, keeping her away from Bucky like that. She yowled at him. "All right," Steve said, unlocking and opening the door, and she shot in like a black streak. Bucky was sprawled on the sofa looking at the lit tree, and Shop Cat immediately scampered up and strode back and forth across him a couple of times, inviting him to pet her; daring him; daring him again. Bucky's mouth curved and he dragged her close by the back of her neck and then roughly rubbed her face, cheeks, ears. She stretched out beside him in satisfied bliss.

Then he looked up and saw Steve. "Oh, hey, sorry," Bucky said, and scrambled up to turn off the music.

"No, leave it; I like it." Steve swung the black bag off his shoulder and took his coat off.

Bucky left the record going, but turned the volume down. "Just, Natasha called," he said. "She's making noise about wanting to do the Swing at Lincoln Center, so I figured I'd..." His eyes found the black bag. "But I don't have to go," he said, and then: "I'm guessing you didn't accomplish whatever it was you wanted to accomplish."

"No, I didn't," Steve admitted. "But it was a nice afternoon anyway. Bucky, I think I'm trapped in the past."

"Stop the presses," Bucky deadpanned. "News flash. We interrupt this broadcast to bring you this breaking—"

"Oh, shut up," but actually being mocked by Bucky always made Steve feel better. "Nobody's trying to make you be the symbol of a whole goddamned nation," he protested. "You don't know what it's—"

"The hell I don't," Bucky snorted. "I let down the whole of Soviet Russia, Steve. 300 million people - and those people have already been let down plenty, believe you me. They've been let down by experts," and Steve grinned and went over to Bucky and opened his arms, offering.

Bucky just stared. "What the hell are you...?"

"Come on, this is kind of a slow one; I can do this one. Dance with me," Steve said, and Bucky lifted an eyebrow but slunk gracefully closer. Steve gripped Bucky's hand and slid his own hand onto Bucky's waist and tugged him nearer, then turned him a little.

"Oh, you're gonna lead, are you?" Bucky asked.

"You think I can't?" but in fact Steve wasn't interested in doing any fancy steps; he just wanted to pull Bucky close and dance slow for a while. And Bucky seemed to understand this, because he pressed in and slid his arms around Steve, and held on tight, their faces brushing together.

"It's okay, you know," Bucky murmured finally, "if you want to live in the past."

"No, it's not," Steve said. "Not if I'm being a roadblock to my own life."

"You're not; you're an artist—you're a good artist, Steve. You should do another show—"

"Maybe, but that's...it's just part of who I am. There's something missing somehow, some part of me that—" and it was like talking to Tony had knocked something loose, because all of a sudden it was clear; he could see it: "It's like some part of me died when I became Captain America and I can't get it back." He stopped dancing; he was suddenly on the verge of tears. "I don't even know what it was, so I don't know what fits in that space. It's a hole, it's just gone."

Christ, he had to pull it together; he could tell from Bucky's alarmed expression that he had to pull it together. "Steve," Bucky said, low and sincere, "I'm so sorry," and Steve pressed in and turned his face away.

"No, it's all right—I'm just being dramatic. Peggy would kick my ass," Steve managed, roughly brushing wetness from under his eyes. "I've got no goddamned excuse: you've managed to figure out who you are, Buck, even after everything they did to you. You don't live in the past."

"Hell, no," Bucky said. "I don't want to go back five minutes. I want to get as far away from the fucking past as possible. But I thought it was different for you." Bucky surprised him by dropping a kiss on Steve's bearded cheek and murmuring, "To the future, pal—it's the only way."

"Yeah," Steve said, and then: "Hey, I forgot; I brought you something." He disentangled himself, went over to the cymbal case and pulled out the Bruce Springsteen album. He offered it to Bucky, who took it, glanced down at the cover, and burst out laughing.

"Born to Run," Bucky said, and then: "Ahaha. No."

"I'm willing to look to the future," Steve said, grunting a little as he fixed the ninth nozzle into place, "but is this the future?"

"This is not the future," Bucky told him firmly. "This is self-indulgent bullshit." He had nearly finished tiling one wall of the bathroom. "But there are some good things in the future," he said, scraping hair out of his eyes with his wrist. "No flying cars—but I like having a pocket telephone, even if people have no manners when it comes to using them. I like YouTube—"

Steve lowered his wrench. "You like YouTube ?"

"I do! You can learn anything on YouTube, it's like free college. They'll show you how to fix a transmission or make beef bourguignon or you can listen to an economics lecture halfway across the world. The International Space Station is amazing. Cordless tools are amazing. I have a personal appreciation for Kevlar. And—well, you won't like this," Bucky muttered: he had gone back to setting tile, "but the weapons are better here in the future. I had a Barrett M82 that was so accurate you could cry. I can't believe I ever hit anything with that old Johnson. Today's Glocks make the guns we had look like pea shooters." He sat back on his heels and considered his work. "Does that look good?" He thought it did. "Modern medicine is a goddamned miracle. I'm personally happy to live without TB, Spanish Flu—"

"Polio," Steve chimed in.

"Polio," Bucky agreed, ‘yeah; fuck polio. And then, consider the vast improvements in—"

"That's it, you got it," Steve said suddenly. He looked over at Bucky. " Tony's not a soldier."

"That's true," Bucky said, "but so what? What are you talking about?"

"I'm an idiot," Steve was muttering. "Tony's not a soldier. It needs a soldier," and then he was worming his phone out of the pocket of his jeans and pressing buttons. "Hey," he said, "any chance you're free to see me? Now. Or as soon as—" He glanced at his watch. "An hour, maybe?"

Bucky shook his head: that was the thing with phones. No goddamned manners.

"Yeah, I can do that," Steve was saying. "Yes. Thank you," and then he looked over and said, a little pleadingly, "Buck—"

"Go on, go." Bucky rolled his eyes and waved a hand at him. "Do what you gotta do."

Steve hauled himself up and said, a little apologetically, "I did finish the..."

"Yeah, yeah. Gimme the keys to the van," Bucky said, and Steve threw them over.

"Thanks, Buck. I'll check in with you later," Steve said, already heading for the door.

"Yeah, okay," Bucky said, spreading some more adhesive on the trowel. "I'll be here," he said, and then calling after him, "you know: earning the money we live on," but Steve was already gone.

The uptown VA was enormous, and busy, even on these days before Christmas. Steve waited on line at the desk and found out where the PTSD group was meeting and went to wait outside that room. Vets of all stripes milled past him: old and young, some of them brimming with health and others, Christ, wrecked if not crushed by the experience of war. Some people used wheelchairs and others had prosthetic limbs, some even more high-tech than Bucky's; one woman had a leg that made her look like she could jump as high as a building. The hairstyles were different but the faces...he could always tell if they'd seen combat, if they'd had the experience of realizing that death was only a moment away, and a person was just a fragile bag of meat.

Finally the door opened and people began to trickle out, and finally there was Sam, wryly looking him up and down with a shake of his head.

"Man, you blow in like the west wind," Sam said. "What's going on?"

"Nothing," Steve said. "I just—wanted to talk."

Sam frowned. "Is Barnes okay?"

"Oh, yeah, he's great; he's fine. It's not him," Steve said awkwardly.

Sam's face lit up in understanding. "Oh. Huh," he said, and then: "C'mon, let's get coffee."

They went to the VA cafeteria and got coffee and sandwiches. Sam was watching him curiously but didn't press him, and Steve found himself trying to figure out how to say what he wanted to say. Finally he said, "Sam, when I went to war, everyone I knew was going. My whole neighborhood, all the guys, Bucky; everybody. And the women and the old men, the unfit like me, we had to run everything all by ourselves, which was hard, not to mention that any day you might get a telegram saying that your son, your brother, your husband, your friend, was dead. But you had to keep going. And in that situation...it was important to do something. Even me: even I had to do something, unfit and skinny as I was. We all had our part to play, do you see? We were a team, the whole country was. Captain America was a symbol of that."

"But that war's over," Steve told him. "That whole situation is over. And I'm not in the army anymore and I don't want to be in the army anymore. But even if I was, it wouldn't mean the same thing. I'm not one of the guys, Sam; I'm a hundred years older than the men and women serving today. I don't represent the situation: it's a totally different situation. A symbol has to mean something, it has to resonate— "

"You do mean something," Sam said, low and forceful. "You represent the best of who we are."

"But that's all history, Sam," Steve said. "And I don't mind being history—history's important!—but there should be a Captain America for the now, too: someone who can serve these guys now." He hauled the black cymbal bag onto the table and said, in a low voice: "They put a balloon of me in the Thanksgiving parade and act like they're treating veterans well: are we treating our veterans well, Sam?" Sam sat back in his chair and stared at him. "Captain America's the head of a team, the whole American team, soldiers and civilians, both: is America a team, Sam?"

Sam didn't reply, but his throat was working, and maybe to distract Steve from that he reached for the bag with both hands and pulled it over. "Sometimes all you can do is get out of the way, give someone else a shot," Steve said—and unlike Tony, Sam immediately unzipped the cymbal case all the way around and pulled out the shield. It was almost ridiculously colorful against the battered old table and the grim institutional paint on the walls, its finish bright in places and scarred and battered in others. There were still blast marks on it from the trainyard explosion.

Around them, the buzz of the cafeteria—the hubbub of conversation, the clank of the cutlery against plates—slowed and then stopped. A young guy in fatigues stopped abruptly next to their table, tray in hand, and said, "Whoa, is that what I think it is?"

From the next table, a woman with a buzzcut said, "Nah, it's a replica."

"All banged up like that? If that's a replica, it's a helluva replica," someone else said.

"That ain't no replica: I got a top quality shield, paid a ton for it, and it's nowhere near as good."

"No, this here is the real thing," Sam said, and people were getting up, coming over, crowding around to look, and Steve smiled and slipped out of his chair to get another cup of coffee.

"Hey," Steve told Sam, "I think we're going to the Lincoln Center Swing tonight: Bucky and Natasha are dancing. You should come. Hell, everyone should come," he added, and pulled out his phone, and that was how later that night he and Sam found themselves wading through a crowd of cheerful people drinking champagne down on 66th Street.

They'd laid out a huge sprung wood dance floor on the piazza and surrounded it with a blaze of holiday lights and heat lamps; on one side was the enormous glowing golden bandstand containing the Harlem Renaissance Orchestra, a full eighteen piece jazz band. Most people were crowded around the edge of the floor, watching the dancers; Steve knew from long experience that you wanted to give swing dancers as much space as possible. Steve made his way through the crowd, keeping his eyes open for Bucky and Natasha, and so nearly ran head-first into Clint, who was grinning and holding a champagne flute.

"Come on," Clint said, waving them onward. "Tony's here, too," and Steve and Sam followed him past two sets of velvet ropes to some tables set up under a long tent at the side of the dancefloor: of course, Tony had commandeered space in the VIP area. He wasn't there, though, and Steve looked the question at Clint, who pointed: Tony and Pepper were out on the dance floor along with the rest of the plebes, laughing and twirling each other around.

Steve looked down and found that someone had put a glass of champagne in his hand. Sam had one, too, and so Steve turned and clinked glasses with him. They drank—he was always surprised at the sharpness of the bubbles—and then he lowered his glass and scanned the dance floor for Bucky. It didn't take long to find him; Steve had always been able to pick Bucky out on the dance floor. It was an up-tempo number, and he was spinning Natasha around so fast it made Steve dizzy just to look at them. Bucky and Natasha were moving not with the giddy drunken looseness of most of the dancers but with tight precision, on the beat, leaning back so far that Steve was always surprised when they didn't fall over, hands parting and meeting and—whoa, she was up in his arms, flying over his head and down again—and they didn't stop dancing for a minute, even as the people around them broke out into spontaneous applause and cheers.

Beside him, Clint downed the rest of his champagne in one gulp. "It doesn't bother you?" he asked, and it took Steve a moment to figure out what he meant.

"No," Steve replied, surprised, and then: "Not anymore. I guess it used to," because he could still remember feeling his stomach twist watching Bucky dance with one gorgeous dame after another, girls groping and pawing and draping themselves all over him, but... "Thing is," Steve leaned in to murmur, "I can 100 percent guarantee you that Natasha isn't going home with Bucky tonight. After that, you gotta make your own luck, pal," and just then the song ended with a crash, and all the dancers broke apart, flushed and breathless and clapping hard for the orchestra.

Then, perhaps to give the dancers a break, the orchestra broke into a slow number, Benny Goodman's Moonglow . "Come on," Steve said to Clint, quickly draining the rest of his own champagne. "Follow me," and then he was moving out onto the dance floor, heading for Bucky and Natasha. He tapped Bucky's shoulder, and Bucky's smile was like a sunrise.

"Hey, you made it," Bucky said.

"Yes, I did." Steve bent to kiss Natasha's cheek, and then said, "May I cut in?"

"Sure thing," Bucky said, stepping away, and then he laughed out loud as Steve grabbed his hand and dragged him into a clench, calling over his shoulder, "Clint! You're on your own!" But Natasha was laughing, too, grinning at Clint and raising her arms to him in invitation, and soon they were each off in their own circle, two couples dancing.

"Well, you're in a good mood," Bucky said, his face all barely-repressed amusement. "Not just dancing but dancing in public?"

"Hey, I made an honest man of you. Or vice versa. Someone made an honest man of someone, and this is all legal now, right?"

"Right," Bucky agreed. "That is another good thing I meant to say about the future."

"It's nice," Steve said. "I like living in the future."

"Me too, pal," Bucky said. "Me too," and then: "But can I lead? Please? "

"Oh, all right," Steve said, and so they switched hands.

They stayed out late, with Tony ordering bottle upon bottle of champagne and all kinds of fancy snacks. They toasted Sam Wilson as Captain America and at some point Clint and Natasha disappeared and then Bucky danced (much more carefully) with Pepper, who seemed to enjoy it.

Finally they hailed a cab back to Brooklyn and Steve sprawled, relaxed and happy, against Bucky in the back seat, feeling Bucky's warmth all up his left side. The stars blurred out the cab window—or maybe it was the lights in the skyscrapers—as they headed downtown toward the tunnel. Steve honestly couldn't remember being so—

Bucky's phone rang.

Bucky sat up, fumbled it out of his coat pocket, and held it to his ear. "Yeah," he said. "Yeah," and then he was pounding on the divider between them and the cab driver and saying, "Pull over; pull over anywhere," and then, to Steve, apologetically, "I gotta—"

"Go," Steve said, and Bucky threw open the cab door and disappeared into the winter night.

"Barnes," said Tony's voice in his ear, "I'm reading your location; stay put, I'm sending you an Uber and a care package," and a moment later a motorcycle roared up the dark street: it was Natasha, looking beautiful and disheveled and really pissed off.

"Not even time for a cigarette," she gritted, and shoved a black bag at him. Bucky took it and swung himself on the motorcycle behind her.

"Hey, lucky you; I didn't get that far," Bucky said, and they were off, zooming into the night.

Tony was saying, "I got an extreme heat signature in Times Square; I'm guessing our aliens dropped a big load of goo just when all the Broadway shows were letting out. These guys are headed for the Great White Way, folks: no more tryouts in the backwaters of Brooklyn—"

"Hey," Clint protested from somewhere. "East New York is very up and coming!"

"We need a plan, people," and that was Sam's voice. "I've got zombies in Times Square and I'm not hearing anybody putting forth a plan."

Bucky touched his headset. "Hey, those zombies are civilians," he said. "They're dangerous right now but they'll recover if we help them so don't fucking kill them!"

"Roger that—I'm calling a three part plan," Sam said, just as Natasha jumped the curb and headed past a rush of screaming, fleeing civilians into the pedestrian part of Times Square. Bucky looked up and saw Sam, wearing Steve's uniform—or he guessed it was Sam's uniform now—standing on top of a NYPD police van with his wings outspread and the shield on his arm. Natasha skidded the bike to a stop as Bucky gaped up at Sam, heart thumping: Captain America looked as much like an avenging angel as Bucky'd ever seen outside of church. The van was rocking beneath Sam's feet: the area around it was thick with stumbling, doped-up civilians.

"Everybody listening?" Sam called out. "Good! Part one: protect the civilians! Part two: poison control! Part three—let's get that damn portal closed, pronto!" and high up in the sky, though it was hard to see with all the bright lights of the Times Square billboards and marquees, something else was glowing; it was like someone had ripped a little hole in the sky.

Bucky opened his mouth to reply, but Hawkeye got in first. "Barnes and me, we'll contain the civilians—we've done it before, we know how," and Bucky replied immediately, "Roger that."

"Good, good," Sam said. "Natasha, you take poison control; Stark, you and me let's fly up and see what we can do about that damn portal." Bucky said, quick, to Natasha, "This is my stop, honey," and then he leapt off the bike, dragging the bag with him, and strode toward the crowd.

"Hawkeye." Bucky unzipped the bag as he walked, taking out its contents and dropping the bag behind him. He affixed his Winter Soldier mask to his face and dragged his holsters around his hips, then went for the gas gun and checked the cartridges. "Have you got my position?"

"I got you, Barnes," Hawkeye said, and then: "Raise your hand in the air like you just don't care," and Bucky rolled his eyes but hefted the gun and fired several smoky rounds into the crowd before raising his metal arm and snatching Clint's arrow, and its attached rope, out of the air. Working together and using the rope, they got the coughing, discombobulated citizens lassoed and corralled: they shoved one group into a nearby Foot Locker, another into a hastily-evacuated Starbucks, and another group into the Disney store, and sent the metal security shutters rattling down to trap them inside.

Bucky's earpiece crackled. "Guys, this stuff is incredibly toxic," Natasha said, sounding revulsed, "but I've got it contained. We need hazmat," and like she'd made them appear, the area was suddenly overrun with SHIELD Hazmat officers as well as cops in gas masks—and then suddenly above him there was a loud pop like a lightbulb exploding. Bucky ducked reflexively, aiming upward. Sparks rained down, and through them he saw Sam do a swooping backflip in one direction while Iron Man shot off in another. The portal had vanished; the sky was clear.

Sam shouted, "All right! Yeah! That worked!"

Tony was whooping in his ear: "I hope we burned their eyebrows off! That'll teach them to attack Broadway! We got Hamilton, motherfuckers! Bette Midler in Hello, Dolly! Bruce Springsteen! Hell, we got—" He cut off for a second, then rattled on: "We got another extreme heat signature, in Brooklyn this time," and Bucky felt a chill at the back of his neck; he was already racing across Times Square, heading for a row of motorcycles. "JARVIS, gimme an exact—" Tony was saying. "Atlantic, Flatbush, Ashland, what the hell's there that would attract—"

Bucky was already astride a bike: now he ripped the control panel off with his metal hand and hotwired the engine with two twists of wire. "That's the strip between the Barclays center and the opera house," Bucky told them, shouting a little over the roar of the motorcycle's engine. "There'll be a million people on the street right now." He gripped the handlebars and sped off.

Bucky bent down low and went as fast as the bike would go, dodging and weaving through traffic, knowing it couldn't possibly be fast enough. Hopefully Tony would get there first, and Sam right behind him—but they'd assembled in Times Square in a fucking flash and they still hadn't been fast enough to stop the portal from forming. With this kind of time, the aliens might actually come through, and that would be a whole other kind of fight: a much worse one.

Bucky flew off the Brooklyn bridge, gunned it, then swerved left onto Atlantic and drove straight into a melee, a riot in progress—because while half the hockey fans in Brooklyn seemed to have been turned into shambling zombies, they were meeting fierce resistance in the streets from the other half: Islanders fans in blue and orange jerseys with their scarves tied up around their noses, as well as from the mix of hipsters and swells who'd come out of the opera house.