Scenes from a Marriage: A Month Of Sundays

by Speranza

Author's Note: So this is something of an Advent Calendar for the 4 minute window verse - just a month of Sundays, random bits and pieces, unconnected in any real way: more of a mosaic than a story. My goal is to do one every day (knock wood) between The Immaculate Conception and Christmas. Just for fun (and so I don't kill anybody while grading.) Explicit eventually, the rest as it comes. Feel free to send me your hopes and dreams! Hope you enjoy!

December 8

--green; it needs more green in the--

"Here," Bucky said.

"Yeah." Steve nodded slowly. --black. More green in the-- "Okay," and he looked down and saw that he was holding, not his palette, but a white plate with a sandwich on it. There was a smear of green on its edge, where Steve had grasped it with his thumb.

"Tuna fish sandwich," Bucky said implacably. "Glass of milk."

"Yeah, okay," Steve said distractedly, looking for a place to set it down. "In a—"

"You said that two hours ago," Bucky said.

"I—oh." Steve looked at his watch, being careful not to slide the sandwich off the plate; it didn't seem possible it had been two hours. "Thanks." He dropped his brush in the turps, wiped his hand on his jeans and picked up a triangle of sandwich. "Just I'm losing—"

"The light. I know," Bucky said, "but look, the days are three minutes long now; you've got to deal with it." He gave the painting a long, appraising look; Bucky knew not to talk about work in progress, but his face was a comment in itself.

Steve raised his eyebrows, still chewing his sandwich. "You think it's dark?"

"I didn't say that," Bucky said.

Steve looked at the painting again: it was dark, and the green undertones made it feel sinister, a little; he didn't think he'd meant that. Maybe he had meant it. "What do you think of when you look at it?" Steve asked finally.

Bucky didn't say anything for a moment. "You're asking?"

Steve thought about it for a moment, then said, "Yeah."

Bucky took another hard look at the painting; Steve watched as his eyes moved across it, narrowed, unfocused. Bucky had a damn good pair of eyes.

"Schwarzwald," Bucky said finally, with a shrug of his metal shoulder.

"Yeah," Steve said. "I guess," and then, sighing a little: "The days are only three minutes long now," and Bucky replied, with soft sympathy: "Yeah, pal. I know."

"The hell, you guys." Natasha shook her head as Steve poured her a cup of coffee and then took a sugar bowl out of a beautiful and strange-looking oak cabinet. "Here's what I don't get. You're running this business. Steve's painting on the side. James is being Cap in his free time: when the hell do you find time to go antiquing?"

Steve blinked at her. "When the hell do we - what?"

"She's kidding, she's joking; she's yanking our chains," Barnes said, dragging a chair out and collapsing into it with his own mug of coffee. "Shopping, she means: it's just a joke, antiquing, because we're old, get it, so whatever we buy is—"

Steve's face cleared. "Oh: so it's like the fossil thing."

"Yeah," Barnes said, and reached for the sugar bowl.

"No," Natasha replied, "it's not: it's a serious question! There not a thing in this room that's not fifty years old, and every time I come over you've got some new piece that's—I mean, that," she said, because the oak cabinet had three doors of differing sizes and heavy silver hinges and latches. "I've never seen anything like it. Or that big Art Deco wardrobe in the bedroom. Where did you—"

She stopped; Rogers and Barnes were eyeing each other sideways and laughing.

"You tell her," Barnes said, and so Steve, grinning, said, "Natasha, we fix things. That wardrobe was on the street: real walnut, put out on the curb like a piece of garbage."

"To be fair, it didn't look like that when we picked it up," Barnes interjected. "Steve put a lot of elbow grease into it—sanding and finishing, all the fiddly little inlays--"

"Yeah, but I knew what it was," Steve replied, "so I knew how it was supposed to look, with all the bits and…Cause that's half the— see, that cabinet, whoever had it, they didn't know what it was. So they ripped off the doors, tried to makes shelves—"

"It's an icebox," Barnes told her. "Old style, like when we were—"

"Nicer than anything we ever saw when we were kids!" Steve interjected.

"—kids, but nicer: I was gonna say nicer!" Barnes said, and glared at him. "If you'd let me finish a sentence now and again," and Steve gestured extravagantly: go on, go ahead. "We made new doors for it, and I got the hardware from a busted up piece on a restaurant job. There, I'm done." He looked at Steve. "See? Done. Was that hard?

Steve opened his mouth, but Natasha forestalled him. "So you're saying you guys can just find or make furniture like this?"

Rogers and Barnes looked at each other, shrugged. "Sure," Steve replied. "Is there something you're looking for?

"Can you get me a table? This one you've got," Natasha rapped on the table with her knuckles; hardwood; gorgeous grain, "would cost me about six thousand dollars."

They exchanged shocked looks and burst into very un-Greatest Generation-like giggles. "Jesus Christ, give me five and I'll put it in the car for you," Barnes said.

"That wardrobe's four thousand at least," Natasha said, and they laughed harder.

"Four thousand dollars?" Steve shook his head, rubbing incredulously at his beard; laughing had made his cheeks pink. "Well, I'll be damned…"

"We're in the wrong business," Barnes marveled. "The wrong fucking—okay, for you, today only: four thousand five hundred." She'd never seen him so tickled.

"We'll get you a table, Natasha." Steve sat back, still grinning. "Happy to."

"If you leave a deposit," Barnes said, and Steve laughed and said, "Kidding. He's just kidding. --I mean, I think he is."

Bucky looked down as Steve dropped the magazine on the table in front of him, the event circled in ballpoint:

HOLIDAY SWING at LINCOLN CENTER!

The Harlem Renaissance Orchestra tribute to Harry James

Featuring: the Ambassador Prize Lindy Hop Dance Contest!

"You should take Natasha," Steve advised. "She's trained, you know. You could win this."

"Yeah," Bucky said, craning his neck to look up at him, "because that's how to live under the radar in New York. Spoken like a guy who painted a target on his chest."

Steve looked down and said, fondly, "That's hardly where they're expecting you to be, Buck: winning the Lindy contest and telling the horn players they're off-tempo."

"Point," Bucky conceded, "but still: a handsome guy like me might get his picture in the paper, especially if he won a dance contest. Natasha's not bad lookin' neither, or so they tell me."

"Uh-huh. And you think they read the Arts section? Hell, you think they read the newspaper?"

"Hey, I'll lay odds they can't read period, not even so much as Dick and Jane, but they probably run it all through facial recognition software. A fine looking mug like mine is sure to ring the cherries at Langley or Quantico or—hell, maybe the Kremlin, for all I know. Besides." Bucky pushed up out of his chair and extended his arms, and even with all that metal hanging out of the sleeve of his undershirt he could still manage something like good form. "Who says I want to dance with her?"

Steve laughed. "Common sense? I still can't dance a lick, Buck."

"Okay, so?" Bucky kept his arms up. "Come on, what are you waiting for? I'll show you," and Steve smiled and turned away like he was teasing, conversation closed, and in fact he had been teasing, except for how suddenly he wasn't. Suddenly he really wanted to try dancing with Steve.

So he snapped his fingers and said, "Wait, wait; music," and then he was going over to the phonograph and pulling its lid up, trying to pretend not to notice the way Steve was staring at him. They'd left Rhapsody in Blue on the turntable—or Steve had; sometimes Steve put on the phonograph and left the doors between the apartment and the studio open while he painted—but that wasn't the kind of music he wanted. He slid it back into its sleeve, then quickly flipped through their records—you could get anything now for fifty cents a pop. He and Steve stopped at sidewalk sales and thrift stores, had picked up a collection of Duke Ellington for a quarter, Benny Goodman for a half a buck. He hesitated over a recording of Count Basie's Jive at Five, but only because he had Lindy Hopping on the brain, then impulsively snatched up a copy of Jimmy Dorsey's orchestra doing Besame Mucho. It seemed kind of strange now, everybody having been so crazy for South America, for Xavier Cugat and Carmen Miranda, for rum and coca cola and the South American Way, but it had made sense at the time: he remembered feeling the pounding of drums all through his body, and it had been sexy to rhumba, to tango.

He set the record up and turned just as he heard the first hitch and pop, the hum of sound that wasn't quite sound but wasn't quite silence either. It started slow, with Bob Eberly mangling the Spanish, but he had a good voice. It was definitely a bolero, though—slow and lush—and Steve was biting his lip and trying not to laugh.

"You're not serious," Steve said, just as Bucky pulled Steve's hand to his hip and dragged his other hand up.

"Dead serious," Bucky said and kicked him; "Ow," Steve said, and moved his leg.

"Basic tango: walking steps front and back, then side to side; you got it? Easy peasy: heel to toe, toe to heel, three steps forward, three steps back; then side-side. Okay?"

Steve was laughing under his beard, the bastard. His eyes said try me, and hell, that was familiar enough. Steve'd do anything if you dared him. "Yeah, okay," Steve said, and firmed his grip. "Who leads?"

Bucky flashed him a sarcastic look, then fluttered his eyelashes a bunch of times. "I'm secure, buddy," he said. "You go on ahead."

"Okay then," Steve said, and suddenly his brow creased and his face was full of determination, like he used to look when he was small and gearing up for a fight, but instead he marched Bucky backward three steps, and then pulled him forward three steps, and then they went side to side and stopped. On the record, Bob Eberly was warbling, Beeeesaaaame mucho / hold me my darling and say that you'll always be mine.

"Not bad," Bucky said, and then they were both laughing. "A little mechanical, and you could maybe look a little less like you were waiting to get a tooth pulled. Also, why'd you stop? That's just the first--" and Steve glared and lurched into motion again, pushing through the steps, grinning and biting his lip, and Bucky closed his eyes, smiling, because Steve wasn't a very good dancer but he was, and so he knew how not to resist, how to just let Steve move him three steps back, three steps forward, and then side to side as Besame Mucho abruptly bopped into swing, with Kitty Kallen taking up the lyrics in her warm voice.

Whoever thought I'd be / holding you close to me, and he felt it the moment that Steve realized that he could move Bucky however and wherever he wanted, that Bucky would follow him anywhere, and he registered the slight change in pressure on his hands, on his waist, as Steve geared up for a turn and then turned him, and for a few moments they were really dancing and not just fooling around, Steve pulling him close, and with the horns blowing and Steve's beard brushing his cheek, he could almost believe it was 1944 again in some alternate universe where the Japs hadn't invaded and everyone was queer. And then he was pedaling backwards, eyes flying open, and Steve was breathless and flushed and shoving him back against the table and pushing their hips together, and he was hard, Steve was, and okay: the horizontal tango was good, too.

Bucky licked his lips and tried to keep his cool as Steve gripped him through his pants. "You want to take the lead here, too, boyfriend?" and Steve's blue eyes flashed again - try me - and that was a yes.

Steve had nearly—nearly—got the cage screwed into the bottom of Ann O'Reilly's new faucet, which wasn't difficult so much as it was awkward, being that the cupboard under the sink was less than two and a half feet wide and he was trying to work around the pipes and the P-trap and the giant block that turned out to be the InSinkErator or whatever the hell they called them these days. Steve lay on his back, the edge of the cabinet digging into his kidneys, and he had just gotten the cage threaded when he felt the vibration—phone, front jeans pocket—and damn it, if he stopped now he'd have to do this all over again. But Bucky was the only one who had his number, and sometimes it was just "don't forget to pick up tacos and beer / the laundry / two bags of concrete on your way home," but sometimes it was giant bats on the Brooklyn Bridge or an explosion in Jackson Heights, and Bucky was running off to risk his life as Captain America.

That was its own sort of ache—Steve had wanted out, but he hadn't anticipated Bucky stepping in, and so now he had that to worry about: this isn't payback, Buck, is it? Except he knew that it wasn't: Bucky wanted to do it, needed to. It was maybe even the thing that made their happiness possible, because Steve suspected that Bucky was setting every act of sacrifice or good deed against some dimly-remembered horror he felt responsible for. He and Natasha were a lot alike, in that way.

Steve sighed and slid out of the cupboard, hip still vibrating, and wormed his phone out of his pocket. He vaguely noticed that Mrs. O'Reilly had been standing at the entrance to the kitchen, watching him; this happened sometimes. She quickly ducked out.

Steve pressed the green button and raised the phone to his ear. "Hey," he said.

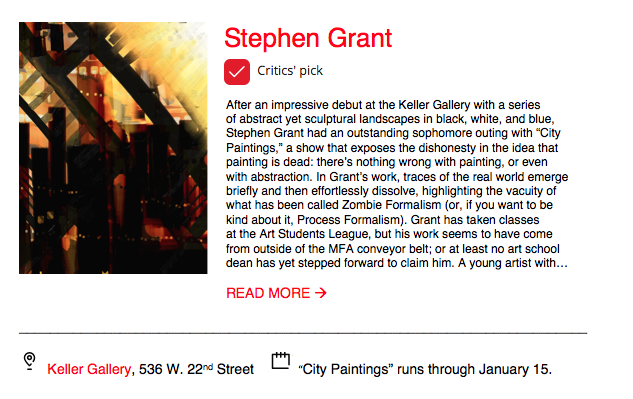

"Hey," Bucky replied, faraway in his ear. "You're on the ARTnews list of painters to watch," and seriously, if Bucky'd delivered this news in person, Steve would probably have thumped him—which was probably why he'd phoned, come to think.

Steve looked despairingly at the pieces of faucet. "That's why you're calling?"

"Yeah. It's pretty good write-up, too: they're saying your work is a blow against Zombie Formalism—"

"You jerk, don't tell me that! I can't believe you convinced me to show in the first place," Steve hissed, with a narrow glance at the doorway, "because you know I don't care about--whatever, reputation - and besides, like some asshole's always telling me: it ain't the way to lie low in New York!"

He could practically hear Bucky's eyes roll. "What, you think they read ARTnews?"

"No, but I wouldn't've figured you did either," Steve shot back.

"I don't." Bucky sounded vaguely offended. "God. I wouldn't be caught dead reading that rag."

"So how did you find out about—" Steve frowned; he sometimes forgot that Bucky'd been a spy as well as a soldier; he was like Natasha in that way, too. "You been keeping tabs on me?"

Bucky barked out a laugh. "In ninety thousand ways, pal," he replied, "but this was just a Google alert."

"A what?" Steve asked.

"Oh, Jesus Christ, join the 21st century, would you?" Bucky said, and hung up.

Steve sighed and went back to installing the faucet. When he was done, he cleaned up after himself and made sure the new sink was clean and all the chrome bits were shiny. Mrs. O'Reilly looked pleased with the work; almost too pleased, he thought—it was only a faucet—though she seemed to bring herself back under control when her husband appeared in the kitchen.

"Oh hey, thanks," the guy said, and swung out a hand; Steve quickly wiped his on his jeans before shaking. "You saved me a job there; I'm hopeless at that stuff, and so Ann said, you know: let's just hire someone. How much?"

Steve told him and directed him to make the check out to Coney Island Design and Construction. The guy bent over the counter to write it out, and then frowned and looked up at Steve—and then down at the check and back up at Steve. Steve went cold inside, but forced himself to stay calm, relax, keep his shoulders down. He had to keep his face together, not give anything away.

The guy finished writing the check and carefully tore it out, though he hesitated before handing it to Steve. "Sorry," he said, openly studying Steve's face now, "but did anybody ever tell you that you look like—"

—and Steve had a sudden, intense longing for things that weren't even gone yet—the shop, the studio, the dogs, Shop Cat—though Christ, he'd give up everything if he could keep Bucky: please God, let him keep Bucky—

"—Tom Pyatt? He's the forward for—do you follow hockey?" and it felt like his body was melting, ice slipping off his shoulders: thank God, thank God, thank God; thank you, God.

"Yeah," Steve said, and managed to smile as he folded the check and tucked it into his pocket. "You know. I get that a lot."

Motherfucker! And he was lucky he had any eyebrows left, dumb fuck that he was, leaving the fucking secondary carburetor blades open; he was lucky the backfire hadn't taken his goddamned face off, ruined what good looks he had left: two eyes and a nose. Thank god the air cleaner had stifled the fire and—

He grabbed a wrench and swung it at the engine in frustration. And he didn't realize that Steve was there until the wrench was suddenly arrested mid-air. Steve yanked the heavy steel from his hand, and said, "What the hell are you—don't beat up the car! That's half my car!"

"I nearly burned my fucking face off!" Bucky shouted, and took a swing at him. Steve blocked him effortlessly, and then they tussled for a moment, testing strength against strength, and Bucky tried to get him into a headlock like he used to but Steve was twisting and writhing and trying to get under his armpits like he used to when he was just a skinny blink and not a six foot two wall of muscle. But they were Bucky and Steve, Steve and Bucky, not Captain America and the Winter Soldier, not fighting for their lives or for their masters or for anything except the sheer lazy Sunday orneriness of it--and suddenly Bucky was dizzy with gratitude, and he shifted his grip on Steve to grab hold of him, clutch at him, ruffle his hair, and it took Steve a second to realize that he was going for a hug and not a headlock, and then Steve was hugging back roughly, dragging him around and really nearly lifting him off the ground. It was kind of hilarious as well as miraculous, that this had happened to Steve: his best pal since forever and the tiniest, toughest kid in all of Brooklyn.

"You dumb cluck," Steve said finally, and pushed him away. "You could maybe ask for help maybe," and he saw three Steves at once: in triple vision: the punk he'd roamed the streets with, and the golden Adonis who'd charged in to save him, and now this guy, his business partner, who was hidden behind a beard and glasses and a loose shirt smeared with paint: Steve, his Steve. Bucky smiled and wormed a finger into the front of Steve's shirt, where a button had gone missing, and stroked down the line of hair there: soft skin over muscle.

"You popped a button," Bucky said, and worked his tongue into the corner of his mouth.

"Yeah, wrestling some idiot," Steve said, but he was flushing a little, and Bucky was maybe going to hell for it, but it'd always given him such a hard on to turn Steve on. Even when they were kids, or maybe especially then, when pleasure'd been so hard to come by. It had been such a trip to make Steve's tough little serious face dissolve, to hear his breath catch and see sweat break out along his hairline. Bucky'd told himself that it was okay, just temporary, a favor really, because the girls weren't exactly lining up for Steve, but eventually he'd come into his own and find himself a sweetheart. But what he hadn't counted on was his own weakness: that he would fall hard for Steve and be unable to hide it, even from himself. And Steve wasn't a guy who'd leave you in a fight, even if it was your own nature you were fighting.

Bucky turned his hand and used his thumb to unbutton the next two buttons of Steve's shirt, then slid his fingers under the waistband of Steve's jeans; Steve had come into his own and no mistake. "I'm sorry," he said. "I lost my temper when the goddamned engine caught fire." He bit his lip and thumbed open the brass button. "But I'll make it up to you."

"By sewing my button back on?" Steve asked, and he sounded his usual wiseacre self, but his cock was filling, pressing and shifting against the zipper even as Bucky tugged it down.

"Yeah, sure," Bucky said, and gently pressed him up against the Studebaker. "That, too."

Steve came awake to the smell of bacon and coffee and the covers flung back on Bucky's side of the bed. He rolled over, stealing Bucky's pillow and tucking it under his head, and tried to doze off again, but it wasn't as fun sleeping in without Bucky sprawled warm beside him, and besides—he opened his eyes and sighed; it was barely light outside—why was Buck up so early when they didn't have to work today?

He got out of bed and went to find out, not bothering to put anything on over his undershirt and boxers. Bucky was sitting at the table—their million dollar table, as they'd taken to calling it—not just fully dressed, but in construction boots and a long-sleeved flannel shirt; dressed for work, in other words. He was drinking coffee and reading the paper, but he looked up with a guilty expression when Steve came in.

"Hey. I couldn't decide whether or not to wake you, so I flipped a coin and made bacon." Bucky gestured toward the stove, where the bacon was cooling on a rack; there was also a plate of scrambled eggs sitting beside the percolator. "Figured that would bring you out or it wouldn't," he said, shrugging. "Take it all," he added, as Steve went to get another plate. "I've had mine already; I've been up for a while."

"Are you going somewhere?" Steve asked as he set down his breakfast and pulled out a chair.

"I—yeah. I didn't know if you'd want to come with," and then Bucky fiddled with his coffee cup and came out with it. "I told Lalo and those guys that I'd help them decorate Holy Innocents," and oh, so that was it. Steve nodded and took an enormous mouthful of eggs so he wouldn't have to say anything, and waited to hear more. "Just it's a big job, you know, the way they do it," Bucky said finally, "stringing lights, hanging wreaths. It's a 60 foot ceiling, so you know: you need big ladders, people who know what they're doing."

"Sure. Break your neck otherwise," Steve agreed, and ate three pieces of bacon at once.

#

He watched Steve shovel food into his mouth, knowing that he meant to be kind, but he was pretty sure that Steve had the wrong end of the stick about this. They'd never talked about church, or God—not once since they'd moved here, even though you could sometimes hear three different sets of bells on a Sunday morning: Holy Innocents, the Episcopals, and the Methodists.

Bucky knew from surveillance that Steve had gone to church more or less regularly in D.C., though it seemed more like a habit than anything; Steve didn't have much of a life there beyond jogging with Sam, the library, and church. But the first Sunday morning after he'd brought Steve back to Coney Island Avenue, Bucky had waited for Steve to suggest Mass—and the truth was, Bucky probably would have gone if he had, if only to give thanks for a kidnapping well concluded. But Steve had made no such suggestion; in fact, he'd just rolled over and stuck his face in Bucky's armpit and gone back to sleep, and then later, when Bucky'd finally made to get up, Steve had yanked him back and, Christ, had done things to him that showed that he wasn't so much thinking about church. Steve had kissed and sucked his way down Bucky's body, and he'd been in the early days of growing his beard out, so the scrape and burn had been fierce, not that Bucky was complaining. He'd been so preoccupied with his own libido that he'd forgotten about Steve's, forgotten how pushy he could be, but it had all come flooding back—memories of Steve dragging him past his mother's bedroom door, Steve breaking into his room in Italy, refusing to take no for an answer. That Sunday Steve had him halfway off the bed, fucked him until his shoulders slid off and he was hanging upside down and all the blood that wasn't in his cock rushed to his brain. He couldn't remember if they'd made it out of bed at all that day, come to think.

Of course, in those early days, Steve hardly left the garage anyway; he'd been lying low, waiting for his beard to come in, and of course they'd both been half-awaiting a SWAT team; dogs; a helicopter. And then, once Steve was out and about, and it became known on the block that Bucky had un novio, church hadn't seemed to fit with the life they were building. It had occurred to him to wonder if Steve wasn't going to church on his account, in some kind of solidarity: if he thought Bucky was too angry or ashamed or something. And sure, Bucky was angry and ashamed, but not in the eyes of God. He no longer believed in God; hadn't since the war.

Bucky looked across the table at Steve, who was eating eggs and watching him with intense eyes, and said, "I keep thinking, you know, of what my father would do," and saw Steve's face change.

"Oh." Steve's fork stopped in mid-air; he seemed to have forgotten he was holding it. "Yeah," Steve said, and then, a long time after that: "I know what you mean."

And Bucky knew that Steve did, too, because that was maybe the second thing he'd ever learned about Steve back in the day: that Steve had never known his father, that Steve's father had died in the war. Mustard gas, Steve would tell you, tipping his chin up; that was why he was alone and fatherless and had no dad who could beat up your dad, because his father had been a goddamned hero who had died in the war, and Steve was just aching to grow up and do the same. That had been the second thing he'd ever learned about Steve, in their second conversation back in 1926 or thereabouts; the first thing, that Steve would fight you as soon as look at you, they hadn't had to talk about. They had met in a brawl of boys after finding themselves on the same side; one of Steve's endless dress rehearsals for getting himself killed.

"My dad," Bucky said, "if you remember: every year he used to go over to hang the boughs at Perpetual Help," and Bucky's old man had worked hard for his wife and his kids and anybody else who needed him; he'd been a rock, that guy, and Christ, Bucky'd looked up to him. His old man was like Lalo (Gina and five kids and Mass at 9 AM on Sundays in Spanish), like Marco and Dmitri and Yuri and half a dozen other guys up and down the block; family guys, neighborhood guys like he never could dream of being.

"I remember," Steve said slowly, and then: "You're as good a man as your dad was; you know that, right?"

"Yeah, and so are you," Bucky shot back, knowing that it was true, but that Steve would also take it for an insult: because Steve's dad was a hero, and perfect, and dead; and somehow—not for any lack of trying - Steve had failed to become dead, which was all he'd ever wanted to be when he grew up. Bucky huffed out a laugh and covered his eyes; Jesus, it was really a farce or some shit. Steve smiled too, but his shoulders had slumped a little, and Bucky felt sorry, then, and kicked him gently. "You want to come with or what?"

"Yeah, I - sure," Steve said, sighing and sitting back and scrubbing his face. "I mean, it's a mitzvah, right?" and Bucky laughed out loud and pointed at him and said, "Exactly; that's exactly right, pal," and Steve groaned but got up to get dressed.

It took a crew of six guys nearly four hours to hang all of the wreaths and the boughs and the lights in Holy Innocents, and to Father Mendez's delight they finished in time for a noon wedding. They went out by the church's back door, which opened on to the battered concrete schoolyard. It was unseasonably nice out, and they slowed to watch a bunch of kids playing stickball. Lalo nudged Steve and proudly pointed at two of the boys, one at the plate, the other pitching: "Marco and Donato," he said.

Steve smiled. "Fine looking boys," he agreed.

"Yeah, but…But-- Come on," and Bucky was shaking his head in disapproval and going over. Steve laughed and shouted after him through cupped hands, "Aw, Buck, leave them alone, they're only six or—"

"Actually, Donato just turned eight," Lalo said. "Marco's ten," and well, okay, that was something else; eight and ten were serious ages for stickball, and you really had to be doing better than that. Steve watched as Bucky went over to the drain that was serving as home plate and yanked the bat out of the kid's hand, then bent over and started giving instructions. The other kids—Marco the pitcher and two outfielders; they didn't have a full team - started shifting nervously as Bucky repositioned the bat in Donato's hands and shifted his hips and told him to take a few swings, then shifted his position again. Steve smiled to himself; he was having flashbacks to Bucky's dance lessons. His obsession with form was more or less the same.

"Good," Bucky said, as Donato sliced hard at the air. "Better," he amended, as Donato tried again. He lifted a gloved hand to Marco and gestured, come on, bring it, and Marco bit his lip and geared up to throw.

Donato swung, missed, but Bucky snatched the ball out of the air and tossed it back to Marco underhand. "No, that was better," he told Donato. "Next time you'll hit it," and that was true; Donato caught the next pitch square and sent it back in a good, clean line toward third—and Steve, who'd been drifting over that way in a kind of helpless anticipation: he'd been catching Bucky's hits for years—hopped up and caught it.

Donato was jittering happily over the plate. Steve, tossing the ball from hand to hand, said, "Okay, now; hang on a second, no fair," and went over to Marco, who grinned and straightened in anticipation.

Bucky grinned too, licking his lips almost savagely. "You think you can throw something I can't hit?"

"Could be. Maybe." Steve put the ball into Marco's hand and moved him into proper position, adjusting his feet, his shoulders; God, how they'd poured over those newspaper pictures of Freddie Fitzsimmons back in the day. "Join the 21st century, old man," Steve taunted, and then Marco began to wind up for the pitch.

He'd just finished packing up the van when his hip started vibrating.

It had been an easy job, and a pleasant one, fixing the shutters for Nancy Monroe, who was ninety-two and lived alone in an enormous Colonial Revival of the kind that you wouldn't have thought was in Brooklyn if you didn't know anything about Brooklyn. Steve liked the place—maybe too much, actually. It was one of the few places he'd ever gone where he was comfortable immediately, the way he'd been when he'd walked into the home Bucky'd made for them. It wasn't just that Nancy was their contemporary—though she was, and she did things with a habitual and instinctive rightness that suddenly made the ever-present wrongness visible everywhere else (Nancy wrote letters and waxed her furniture and had a card table set up under a lamp and explained, when he remarked on it, that she played bridge with her friends every Thursday and had cocktails, but just one), but also because she'd taught sculpture for almost fifty years at Brooklyn College (her husband had been a dean there) and so had art in a casual, profligate way around the house, things she'd made and things she'd been given by friends: rough clay statues and charcoal sketches and watercolors. He'd been so distracted by this that he'd forgotten his manners completely and just wandered around for a while like he was in a gallery, but when he'd finally blinked and come back to himself, she'd just smiled and asked, "Do you paint?" and he'd admitted he did, a little. He really liked Nancy, and he thought she liked him, too, or at least she kept finding reasons to hire him. Then again, the big old house always needed something, and almost everything had to be hand-made, not that Steve minded. He'd rather carve moldings for Nancy than do another goddamn fake-Impressionist painting.

He wormed his phone out of his pocket and said, "Hey, good timing, I was gonna ask you to pick up—"

"I can't," Bucky said. "I'm on a Quinjet," and all at once the world narrowed to this point, this voice.

"Oh," Steve said.

"There's a thing," Bucky said. "But don't worry—we're vastly overpowered over here."

"Okay," Steve said.

"So it's mostly for misdirection," Bucky said. "And because the Widow asked me to."

"Okay," Steve said, and he knew what Bucky meant by misdirection; they'd both agreed that it would be a bad thing for Captain America only to be seen operating in and around New York, and so Bucky went on whatever away-missions he could: especially missions that Stark or Natasha orchestrated, where they could avoid the CIA or any remnants or reconstructions of SHIELD.

"I might need you to take care of the Zuccos tomorrow," Bucky said. "That's the job with the—"

"Don't worry about that, I got that," Steve said, frowning. "You just worry about—You just—"

"Pal, Tony's here and he shoots lasers out of his ass," Bucky drawled. "We're all gonna be fine," and Steve laughed and said, "Yeah, okay. Call in when you can," and then, a second after the call ended, "I love you," which wasn't a thing that they said to each other, generally; not anymore; because it was somehow a thing that evoked its opposite, like "You're safe," or "I've got you"—things that didn't need saying when you really were safe and the ground was solid beneath your feet. "But I love you," Steve had said, almost angrily, when Bucky'd been trying so damn hard to set him up with Mary Louise Turner one summer; "Because I love you," Bucky had told him, explaining why they couldn't be lovers anymore, back in 1944.

He wished he'd said it now, though. "I love you," he said again. "Dammit," and put the phone away.

He drove back to Coney Island Avenue.

He went out back to feed George and Gracie.

He went upstairs and ate bread and butter, tomatoes and cheese, and listened to the evening news on the wireless.

He put his jacket on and took the dogs to the park for off-leash hours, and watched them run around in the nearly black grass.

He came home, locked up, and took a shower. He read for an hour before turning the lights off.

In the morning, he made coffee and stared at the Kandinsky for a long time. Then he went out to the Zucco place to put up some drywall.

Around 10:30 his phone vibrated, and he nearly dropped his hammer trying to fumble it out of his pocket. He yanked his workglove off with his teeth and pressed the answer button. "Hey, hey, hello," he said.

"Hey hey yourself," Bucky said. "Everything all right at the Zucco's?"

"Yeah," Steve replied, relief leaving him weak. "Everything's fine here. What about you?"

"Fine, good," Bucky said almost absently. "I'll be back around lunchtime - you want to have lunch?"

"Yeah," Steve said, and then, "No. I don't want lunch," he said, and then: "Bucky, I love you."

"I know," Bucky said, low and amused. "Dumbass. But everything's all right, I promise. I'll get those French dip sandwiches you like and meet you back at the house, okay?"

"Okay. Make him give you extra gravy," Steve said. "Also if they have root beer, I want a root beer."

"You bet," Bucky said, and hung up.

"Let's not do Christmas, Buck," Steve murmured, one morning, in bed. "We don't need to do Christmas," by which he meant the presents and the fuss and the hullabaloo. He'd been saying it ever since they were kids and he'd been trying to spare Bucky the expense, because it wasn't like either of them had any money, even thought they'd both worked as soon as anybody would hire them to do anything. Steve had hawked newspapers and Bucky had delivered groceries, and then later, Bucky's dad had got him a job stacking crates at the warehouse where he worked. This was a pretty good job for a kid, though Bucky gave his entire paypacket over to his Ma every Friday, so it wasn't like he was rolling in it, which Steve knew. So: "Let's skip Christmas, Buck," Steve always said. "It's no big deal; every day's Christmas if you're living right."

And Bucky'd always said, "Sure, pal, okay; if that's what you want", because he didn't want Steve feeling obligated to get him anything, especially that Steve didn't have a lot of what'd you'd call earning potential and not even a dad to look out for him. But the thing was that Steve Rogers was a big honking liar who always shoved something into Bucky's hands at the last minute, wrapped in newspaper and a bit of twine. It was always something good too: a battered copy of Spicy Detective or a drawstring bag of real marbles, or a blowpipe and darts, and then later Steve had given him a real metal cigarette case with a picture of the Empire State building etched on it, and once it was a pack of cards with half-naked girls on the back.

And then, that Christmas they were in Italy, Steve had smiled and tucked something small into Bucky's pocket. It was a piece of paper, but it had been elaborately folded down to about two inches square, and it turned out to be a single picture but drawn in parts so that as he turned and unfolded it, different faces became visible—and there was his Ma and his Dad and Becca and Ellie and Grace, and there he was, himself, standing among them, and they were all of them outside on the stoop of the Barnes house, the number 26 visible on the frosted glass. Steve had even gotten in the big crack on the third step and how did he remember all that detail: the stone over the front window and the battered pot of geraniums: even the pattern on his ma's drapes. Bucky'd sniffed and wiped his eyes with the back of his hand, unfolding and unfolding, and finally, in the lower right hand corner, Steve had signed off with a little self-portrait, done in a totally different style than the rest of the picture. It was cartoonish, almost a caricature: Steve, not like he was now but as he had been, standing there in his too-big clothes and enormous suspenders, with his awkward bony arms and long-fingered hands stretched out like he was framing a picture. He was standing besides an old fashioned camera, on a tripod, with a drape hanging off the back - portrait of the artist as a young punk - and so Bucky'd carefully folded the whole thing up again and tucked it into his shirt pocket right over his heart - and seriously, what was one measly Kandinsky against that?

"Sure, pal, okay," Bucky said, closing his eyes and trying to tug the blanket up over his shoulder, "if that's what you want," and he heard Steve's satisfied grunt as he shifted beside him, huge and warm and taking up all the goddamned covers, the lying punk.

Steve parked the van down the block from the battered old apartment building. Bucky unlatched his seatbelt and pulled his notebook from the pocket of his flannel shirt. "This is it, 185 Quincy," he said, flipping through to double-check the address. "What do they want, kitchen?"

"They didn't say," Steve said, yanking the keys out of the van. "'Estimate for work on my apartment, can you come after hours because I work late. I said we could."

They got out and slammed the van doors. It had been dark for hours already, and so it felt like midnight even though it was barely seven, because the days were just three minutes long now. They walked up the sidewalk toward 185; tree roots had lifted the concrete in places, like a miniature earthquake, and weeds grew through the cracks.

"There's a lot of nice buildings around here," Bucky said, looking around. "It's a shame so much of it's gone to shit. Look at that brickwork," he said, pointing; and Steve saw beautifully detailed arches around the windows; chunks of the stone were missing, though. "And the mosaic in that foyer. I'd rather fix that than work on another rich lady's kitchen, any day. We can put it around that we work cheap. "

"Better do it fast," Steve advised. "The hipsters are coming: I think I saw a muffin shop back there," and Bucky laughed and peered down at the panel of worn buzzers outside the door. He pressed 3H and there was a crackle of static from the speaker; the whole intercom system had seen better days.

"Coney Island," Bucky said, and nothing happened. He looked at Steve, who tried the grimy glass door, but it was locked. They waited for a moment, then Bucky buzzed again—bzzt! bzzt!—and this time there was a long, answering bzzztttttt and the door unlatched. They went into the black and white tiled foyer and climbed the steps to the third floor; there was no elevator. "Well, there's work here anyway," Bucky said.

The door to 3H had recently been painted an industrial gray, though there were so many layers of paint on it—on it, on everything—that it had a kind of rounded look. Steve pressed the black plastic doorbell under the peephole and heard a faint chime inside. "I hope this isn't a waste of—"

The door opened, and Steve started, and then laughed. "Jesus," he said, as Natasha pulled the door open. "You could have just called," he said, as she stepped back and waved them inside. "You could've just—"

And then the smile fell off his face, because Clint Barton was standing there, looking awkward.

"Hi," Clint said, and for a moment, Steve didn't know what to say.

He hadn't seen Clint since the party at Stark Tower, the night before he ran away. A charity event, something with Africa: Steve hadn't really been paying attention. His mind had been full of plans and nervous anticipation. Bucky was coming for him. He was going to get out. It was like Grand Central Station in here—and suddenly it was all back, the paranoia, the sickening dread. Clint was watching him; Clint had been sent there to watch him.

"Hi," Steve said finally, tensely, just as Bucky muttered, "It's not cricket, Natasha."

She sighed. "I know, but I wasn't sure he would come if—"

"That's why you ask. That why you should have asked," Bucky said, and then he was drawing Steve aside and saying, low, "You want to go, we'll go. We'll go right now," and part of Steve did want to go, to just walk out and drive away and maybe just keep driving: he was roiled inside, irrationally angry, or maybe it was scared, this feeling; his heart was pounding fit to beat the band. Which was ridiculous: Clint was his friend, and Clint was Bucky's friend now, and besides, it was Natasha who—

"Let me talk to her," Steve muttered back. "I need to—" and then he was taking Natasha's arm, and she was sighing and letting him tug her out into the hallway. He heard Bucky say, tiredly, to Clint, "You got a beer or something?" and then: "Nah, that's him, not me. I got the second rate serum that lets you get oiled."

"Steve, I'm sorry." Natasha raised her hands the moment they were on the other side of the thickly painted door. "I am. Just, Clint and me…he's important to me. And besides, you guys are practically neighbors—"

Steve's throat was so tight that he could barely get the words out. "Did you tell him? Where we are?"

Natasha held his eye. "No," she said.

Steve balled fists in his pockets, resisting the urge to put his hands on her. "Did you tell anyone else?"

"No," she said. "Steve, I wouldn't."

"The van's outside; the license plate. The name of the company—" and now Natasha was putting her hands on him, sliding her palms up over his shoulders like she was gentling him and saying, "He doesn't know, Steve; nobody knows. Just me and Tony—"

Steve jerked back. "Tony?"

"I didn't tell him," Natasha said immediately. "He knew. Maybe James—" She tipped her head toward Hawkeye's closed apartment door. "They get on, him and Tony; go figure. He gets on with Clint, too."

The strangling was easing, now; he felt he could breathe; he felt sorry. "That's good, I'm—glad about that," Steve managed. He swallowed, licked his lips. "So—does Clint really live here or…?"

"Yeah," Natasha said unblinking. "He does. I think you had something to do with that, actually. After you left, he came out here, bought this building. I think he thought, hey, maybe I could have a life, too."

"Sure," Steve said. "Why not? Lives for everybody," he added expansively.

"Yeah." Natasha bit her lip and then said: "You know, you really did a number on us. All of us. You were the heart of it, you centered us, you—"

"Bucky is," Steve began uncertainly.

"Bucky is a great Captain America," Natasha said, "but he's not you, and he'd be the first to say it."

"I can't," Steve scraped out.

"I know," Natasha said.

"I mean, I really can't," Steve told her. "Not anymore. Bucky can, but I—"

"I know," Natasha said, "and we'll go on without you. But we miss you: we all miss you," and Steve wasn't at all surprised to find himself kissing her, because there was always an even chance of it: he was never sure if he wanted to kiss her or strangle her or cry in her arms. There'd always been a strange too-muchness between them, threatening to overflow at any minute. Then she snorted and pushed him away and said, "So come and have dinner with Clint. We'll play cards. I mean, you're old guys, right? You play cards?"

"Name your game," Steve said, managing a smile, "and I will beat you, poker face or no poker face."

"Oh, yeah?" Natasha said, mouth curving into a smile. "Don't bet on it," and then she pushed at the door, frowned, and then hammered on it. "Oh crap, we're locked out."

"So I told him," Steve said afterwards, driving them home in the van.

Bucky's head jerked around. "Who, Clint?" he asked warily.

"Yeah. After dinner, in the kitchen. I told him about the garage and the company." Steve looked across the van at Bucky. "Did you tell Tony?"

"Yeah. Hey, I owe him twenty million dollars," Bucky said, "the guy was due some collateral."

Steve groaned. "We're terrible fugitives," he said, and banged on the steering wheel. "We're the worst fugitives in the world. "And you know what? It's your fault," Steve said, glaring at Bucky. "You and your atonement. Next time we go on the run, no atoning for your years as a brainwashed assassin. It's drawing attention."

Bucky looked at him. "What, you think you're funny?"

"Kind of, yeah," Steve said.

"Well you're not. You're gonna hurt yourself with that. Stop it before you break something important."

"I'm funny," Steve protested. "I'm actually very funny. I'm stealth funny. It's my secret weapon."

"Yeah, I've seen your secret weapon," Bucky snorted, "and that ain't it."

Steve bit his lip and focused on driving for a moment; he wasn't going to let this asshole win. "You know, I'm shocked, really, to discover after all this time that you have no sense of humor. I feel kind of duped."

"You're funny looking," Bucky offered, consolingly. "Your nose is funny. I mean, it's better now that your head's bigger, more in proportion with the rest of you, and it also helps that you're growing that fur on your face—" and that was it, Steve guffawed, letting his head hang, but Bucky didn't so much as crack a smile, "—in fact, I think you should try growing it over the top half, too: cover the whole thing up like the Wolf Man—"

"Stop," Steve gasped. "I'm gonna break something important."

"I've got to try," Bucky said then. "I've got to. I just - I can't stand it otherwise."

"I know," Steve said.

"Us getting to be happy. Getting you; this; everything. Got to pay the tab, right? Someone's got to—"

"You've paid, Buck," Steve said. "You and me both, we've paid enough."

"Not me; not yet," Bucky said. "Look, I know it's a risk, and I'm risking you, too. It's the door to the old life, the door they're gonna try to come through to get at us. But I can't stop. And I mean - you brought the shield."

"Yeah," Steve said.

"You brought the shield out with you."

"Yeah, I did," Steve said, and then: "I don't know why I did."

"Sure you do," Bucky said. "Thing like that, it doesn't sit in a drawer."

"No. I guess it doesn't."

"I want pie," Bucky said suddenly. "You want to stop at the diner? I want pie and a cup of coffee."

"Sure," Steve said. "I could do with some pie," and then: "Will it ever be enough, do you think?"

"I don't know," Bucky said, and frowned. "But I think so. I think I'll know when it's enough," and Steve thought that he might actually start scoring tally marks on the wall, like a convict.

"Heat's coming up," Bucky muttered sleepily; he'd felt Steve jerk awake in the dark and go tense, not registering that he'd been woken up by the old pipes, banging. "S'just the steam," he said, and rolled to slide his arm around Steve's narrow waist.

Steve relaxed and moved back against him so they were pressed together, back to front. Too much, Bucky thought, closing his eyes and pressing his face against the back of Steve's neck; too lucky to be snugged up with Steve in the early hours of a winter morning, with all the bills paid and the heat coming up. Bucky murmured against Steve's warm skin, "We used to know what to do when it got cold and dark," and Steve pulled Bucky's arm more firmly across his body, like he was wrapping himself in it, shielding himself, and then twisted his head back, a little. "Please," he said.

Please - and hell, Steve could be pushy when it came to sex, but some things he just couldn't ask for - not out loud, anyway - and so Bucky knew that when Steve said please like that, he meant--

"Sure, yeah. I want to if you want to," Bucky said honestly, though Steve had to know that his heart was already pounding, his cock filling, and oh, Christ, Steve maybe had all these new muscles up top, but he had the same slim hips that he'd had before, the same smooth white skin. Even now, sliding his fingers inside the loose elastic of Steve's pajama bottoms sent him back to being fifteen and in a constant state of ashamed and confused lust. For a boy, for his friend: a tiny shit-kicker who always needed a haircut. Because he looks like a girl, he'd told himself a little desperately, except for how girls didn't have scraped up knuckles and bloody mouths, didn't have sharp hipbones and dirty fingernails and blond stubble that you could feel, God, when you kissed him. He'd never been able to keep his hands off Steve. For practice, he told himself. Because he was there; because he was small. Because he looks like--but that wasn't it; that was the opposite of it. Because he's a boy, and maybe Steve had the slimmest hips and the smoothest ass, but Bucky wasn't pretending there wasn't a cock hanging on the other side of him; he knew there was, he'd had dreams of it.

He'd tried to save Steve from this, from him, but Steve had just dived in, all recklessness. Fucking had been Steve's idea, too; Bucky'd never have dared it. He'd teased himself between Steve's legs, sure, but it was Steve who'd taken them past teasing, Steve who'd pushed back on him, taking him in. Now he had Steve face down beneath him, gasping, his pajamas skimmed off and Bucky's fingers in him. Patience: Christ, he needed patience and Vaseline and to keep fucking breathing, because all Bucky wanted was to crack him open: to push into him and wrap his arms around him and fuck him till he was blind.

Bucky bent to kiss and bite Steve's shoulders, to drag his mouth along all the twisting, jumping muscles of his back - and then he was running his hands down Steve's body and tugging up the narrow pale hips and rocking, slowly, into him: in and out, going deeper each time. Below him Steve was braced, head hanging and urging him faster, but Bucky tightened his hands and set a steady rhythm, gently changing the angle and the drag until Steve gasped, and that was it, then; he was able to let go. And as they fucked there in the darkness, gasping and laughing and sweating and shouting triumphantly, they were momentarily, blissfully, as young as their bodies; because when all was said and done, they'd both been shocked into immortality by what had happened to them, flash frozen into a terrible youth, forever.

"So what do you think?" Steve asked finally, and when Bucky looked up, glaring, he shrugged helplessly and said, "I know, but—"

"What do you want me to tell you? You're right; we're the worst fugitives in the world," Bucky said, rolling his eyes, "but that said, it's not a terrible plan. So this is who, again? Sam's mother's cousin's—"

"—husband's family, yeah," Steve said. "They own a restaurant in Harlem, and they hold a fancy holiday party each year. Hundreds of people, Sam said: family, friends, clients, vendors. I mean, we know where that is; we've worked up there, we've parked up there. There's no reason we couldn't, you know—turn up at a party like that. We turn up, Sam turns up…" He shrugged. "We have a beer, couple of canapes…"

Bucky considered this. "How fancy?" he said finally.

"I don't know…ties? Ties, I guess," Steve said. "Ties and jackets, maybe."

Bucky leaned back in his chair. "I'll go if you wear a suit."

"I don't have a suit," Steve replied, frowning.

"You can wear one of mine. I have two," Bucky said.

Steve crossed his arms. "Of course you have two; when the hell are you buying suits?"

"Hey, I work," Bucky protested. "I can buy a suit if I want a suit. I look good in a suit."

"Yeah, but you bought two," Steve pointed out. "And for what? Where do we go that we need a suit?"

"Exactly; you're a shit boyfriend," Bucky replied, and Steve whuffed out a laugh. "I bought two because I knew you wouldn't buy one, even, and where the hell am I going to go in a suit by myself? Put on a suit, already, Jesus; make yourself presentable."

"All right, fine," Steve relented. "What about shoes; you got shoes that'll fit me?"

"Sure," Bucky said, grin spreading. "Nice ones."

"Your shoes always hurt," Steve said, scrunching his face up.

"You've got to sacrifice for style," Bucky replied.

"No, you don't," Steve said.

"Yes, you do," Bucky said.

"No, you don't," Steve said, but when they got to Sam's mother's cousin's husband's family restaurant, he was glad that Bucky'd made him do it, because everyone was in suits and fancy dresses, and the place was a swirl of silks and patent leathers and velvet, and some of the women were even wearing hats. When they finally ran into Sam, he was in a suit too, and he looked Steve up and down with surprised approval.

"I'm not saying a word," Bucky said.

Bucky finished his coffee and went across to the studio, where— "Jesus," he breathed, and really, it was his considered policy never to comment on unfinished work, but this—Jesus. Steve was still working in the same colors, but there was nothing representational here, just a nightmare vision of green and black and brown mangled by knife scratches, lines carved into the paint. It felt like all the worst nights he'd ever spent outdoors, huddling with the Commandos in the black forest, or hunkered down with the poor bastards from his old unit, cowering in trenches they'd carved out from the dirt and the scrub.

"Blue," Bucky blurted, and Steve turned to him, wide-eyed and shocked; he had a smear of green paint in his beard. "You—you need blue, electric blue—You remember, like lightning—unworldly—like—like—"

Steve was staring at him. "Like the Tesseract," he said.

"I don't know what that is," Bucky said stupidly, but Steve was already fumbling with his paints, squeezing and mixing them.

"I know," Steve said, grimly sure, and God, he did know—it was just the right sickening color, a pale glowing blue—and then Steve was loading it onto a knife and slashing it across the painting. He added white and gray highlights that made the painted lightning seem to fork and flicker and strobe off the canvas.

"Jesus Christ," Bucky breathed, and took a helpless step backwards, the world lighting up.

"Like that? Bucky? Is that right?" Steve was concentrating furiously, slicing the color in.

"Yeah, I--yeah. Just like that," and his mouth flooded with the tang of metal. He wanted to spit, needed to—and then Steve was there and Steve had him, Steve was holding him, hugging him, impossibly, miraculously large: so much bigger and more solid than he ever was in Bucky's imagination. Bucky clutched back tightly, metal plates shifting along his arm, and said, "You weren't even there that night. They came with energy weapons, tanks and—How are you painting inside my head?"

"It's my head too; they're inside of my head, those colors," Steve muttered back. "Dirt and trees and—the black branches overhead, sniper nests. So many nights in the forest--but the blue, I forgot: the way those Hydra weapons—do you remember the sound they made, charging, and the way the air tasted like—" but Bucky's mouth was already full of the taste, electrical, awful. God, all the years he'd spent with a metal bit in his mouth, and he was gagging a little and Steve was moving fast, half-carrying and half-dragging him down the stairs to the yard. Steve threw the door open and the fresh air blew into his face. He stumbled out. It was like drinking cold water. He gulped at it ecstatically and only vaguely heard Steve chasing away the dogs, who'd come running up, yapping with adoration. Join the fucking club, he thought and laughed.

"Do you want to burn it? The painting?" Steve gripped him by the shoulders. He seemed enraptured by the idea. "We could come out here and set it on fire. God, wouldn't that be—I mean, that would be great, huh?"

"Fuck, no!" Bucky managed, struggling to keep upright. "You could sell that thing for thousands of—"

"I can sell another one," Steve said irritably. "It's not special except for what it means to us; it's only paint, Buck."

"Hang on, I've got to throw up," Bucky said and staggered to the bushes behind the doghouse. He threw up into the flowerbed, then wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and felt better. "Okay, so: you want a bonfire?"

"Yeah," Steve said enthusiastically. "Winter solstice, festival of light: what do you say?" and what could he say, really, because if Steve didn't want to sell the painting--well, he didn't want to look at it himself. And so later that day, the shortest of the year, they dragged some old sheet metal and some scrap wood out of the garage and set up a makeshift fire pit, and then they pulled up a couple of chairs and watched the painting burn, orange sparks flickering like fireflies.

"Hey!" Bucky shouted up the steps. "Come here, give me a hand with—"

The door to the apartment opened and Steve popped his head out. He stared, then came out onto the landing.

"It's not heavy," Bucky explained, shifting the trunk, "but it's awkward, and I don't want to make more of a mess than I--"

"I thought we said," Steve said reprovingly, coming down the stairs, "that we weren't gonna do Christmas."

"Oh, is that what you meant?" Bucky asked, and shoved the top of Christmas tree at him. "I thought you were saying we shouldn't be born in a manger or something." Steve rolled his eyes and grabbed ahold of the tree, and then they began to haul it up the steps and into the apartment. "You say it every year--every year, Steve—and I stopped believing you in, like, 1936 and you're still saying it—"

"Because you don't listen! You say yeah, sure and then you don't listen and—look at this, this is enormous," Steve said, and to be fair, the tree did look bigger in their living room than it had looked on the street.

"You're right, I don't listen. I ignore you, because you always say 'Let's not do Christmas,' and then you get me something even though you said you wouldn't so that I look like an idiot, and then I get us a tree and you say, 'Why did you get a tree?' and then you say, 'Oh, this is nice," and you like it. Tell the truth."

Steve stepped back consideringly, head tilted, and then said, "Well, it's festive."

"Oh, shut up and get me some wood for a stand," and later, they sprawled on the sofa and drank hot chocolate and looked at the tree, which they'd covered with tinsel and bits of colored paper, a box of ornaments from the dollar store. "Do you remember Christmas, 1944?"

"In Italy? Yeah," Steve said softly. "I remember."

"You always got me good presents," Bucky said. "I remember everything you ever got me. But that was the best one." He rolled his head toward Steve against the back of their beat-up sofa. "You got me something, didn't you; don't lie."

"No, I—no," Steve said. "I didn't. I mean, it isn't anything. Not really. Just—" He got up and went over to the sideboard, and when he came back he was holding a little square envelope. He gave it to Bucky, who opened the flap and poured the contents into his palm: it was a St. Christopher's medal on a chain. Bucky stared at it, stirred the necklace with his finger. Steve said quickly, "Bucky, I'm not, I'm not trying to—"

"I know you're not," Bucky said.

"Just you used to wear one."

"Yeah, I did." Bucky picked it up, then hesitated. "Think I'll burst into flame?" and he regretted saying it immediately, because of the hurt that flickered across Steve's face. Bucky quickly slipped the chain over his head and pressed the medal against the base of his throat—no flames - and then knotted his hand in Steve's shirt and kissed him. "Thank you. I'm happy to have it. And I've got something for you, too."

His envelope was bigger and flatter, fatter; manila; tied with a little bit of string around a crackled red button. "There's a woman at the Smithsonian," he said, and handed Steve the envelope. "She's a specialist on—well, you. You and your milieu. Doing a biography, apparently; yeah, another one. I guess that nobody was ever able to find out much about him, but what there is…that's what there is," but Steve had already undone the string, and was carefully was pulling the papers out of the envelope with shaking hands.

He finally worked up the courage to say it. "Steve. I. Look, if you want to go to midnight mass—"

Steve immediately turned to stare at him. "What? No."

"—there are a couple of options. Holy Innocents, St. Catherine's," Bucky said. "And I'll go with you if—"

"Why would you?" Steve shook his head irritably, like there was a fly. "Buck, I know you don't believe."

"So?" Bucky shot back. "There'll be music and lights, art—I'm not a fucking philistine," and that made Steve laugh, anyway. Bucky said, soft, "Just—I would go if you wanted to go."

"But I don't." Steve looked at him. "I don't want to go," and Bucky, confused, searched his face.

"Because you don't believe," he said finally, and shit, he was the one who had it backwards.

"No. Not anymore," Steve said with a sad smile. "I'm maybe sorrier about it than you, but…" He shrugged his shoulders. "What's done is done, I guess. That all—feels like a dream. From another life."

"Yeah, I—yeah. I know what you mean. Are you angry?" Bucky asked.

"No," Steve said. "I mean yeah, I'm furious," and Bucky smiled grimly, "but not like that. I tried—I mean, I did. But it's just gone now. It was just gone one day, faith, like so many things." He looked at Bucky and said, "You know, I could almost believe again because of you. Except for how it makes the Book of Job look like a comedy—"

Bucky barked out a laugh. "A rip-roaring, side-splitting—"

"—gut-buster, yeah; comedy hit of the season," Steve said, sighing and laughing, both. "So you know, I really hope there's not a God, or a scheme, or—I can barely just about handle it if everything turns out to be—" He flailed helplessly.

Bucky picked it up: "—chance and fate," he said, understanding. "Pointless cruelty and bizarre coincidence and fucking incompetence and—"

"—yeah, and man's inhumanity to man," Steve concluded, nodding furiously. "I can just about cope if it's that, but if there's a God involved, then—well, I want a word," and suddenly Bucky was laughing so hard he had a stitch, because that was Steve all over, taking on bullies and picking fights outside of his weight class, and this was the big one, a doozy: Almighty God, if you'd please step outside, Steve Rogers would like a word with you.

Bucky would hold Steve's coat in that fight. He'd bet all his money on Steve, and if that was blasphemy—well, so be it. He was overcome with a fondness so huge it made his chest ache. "Merry Christmas, you whackjob, you nutcase, you fucking lunatic, Steve," he said with breathless sincerity, and Steve cuffed his arm around Bucky's neck and said, "Right back atcha, you jerk, you dope, you filthy, dog-faced fiend."

The End

If you liked this, please leave feedback at the Archive of Our Own and consider reblogging on Tumblr.